AIDS and HIV

‘5B’ nurses: the untold inspirational story of the lost AIDS generation

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – APRIL 30: Julianne Moore appears at the 2019 Verizon Media NewFront on April 30, 2019 in New York City presenting the AIDS documentary ‘5B.’ (Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images for Verizon Media)

This June, LGBT people around the world are commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion that galvanized the steady march toward full equality and LGBT civil rights. Stories are being told about the marginalized gay men people of color, lesbians, and trans folk who’d been harassed, beaten up and derided as sick sexual perverts screamed “enough is enough” and fought back against police violence and accepted societal brutality.

History is being recounted of how gays joined the sexual and political liberation movements of the 1960s and transformed the inculcated, internalized shame of being untouchable into the pride of defiant human truth and authenticity. Freedom was savored during the dawning of the Age of Aquarius and thousands of once despised queers burst out of the closet when religious bigots flooded the political system crying “Armageddon” and demanding the return of traditional values.

But then the stories stop. No one thought Armageddon would actually happen, and no one wants to tell that story anymore. The story of the lost generation. The story of how in the late 1970s, at the peak of the disco era frenzy when self-absorption was an unreflective way of life, death crept in like a burglar and silently, quickly, mysteriously stole gay men from the discos, the bathhouses, the social-family gatherings. Gay men just disappeared.

The hyper-dash to the movement for gay liberation and full equality connects to the early 1980s, when show-offs and body builders turned into terrified, shriveled, wasting away skeletons. No one knew why. And no one seemed to care.

But these gay men, some who fought in Vietnam, some who fought against it; some who became activists after Stonewall, some who took advantage of that activism – many who just danced – succumbed one by one to what took several years for researchers and the government to identify as HIV/AIDS.

In those very dark years of the government’s stubbornly cruel refusal of care, as gay people became pariah’s as “carriers” of the mysterious new disease that some believed could be transmitted through the air or through shared kitchen utensils—brave souls emerged to provide care and compassion to the terrified sick and dying.

That story of compassion, restoration of dignity, that loving grace of one human being to another is the subject of a new documentary, ‘5B,’ about the nation’s first AIDS Ward in San Francisco in 1983. The film opened LA Pride Friday night, June 7, and will have limited theatrical distribution on June 14 through Verizon Media outlet Ryot. Julianne Moore helped promote the film last May at the Cannes Film Festival.

“Young people today don’t realize what that was like. It was mysterious. It was frightening. People came in very sick and they died quickly,” Dr. Paul Volberding told the Los Angeles Blade in a recent phone interview. A researcher and clinician, Volberding headed the AIDS Ward at San Francisco General Hospital.

“Before we knew about HIV or had any test for it, people didn’t know they had anything wrong until they often got very sick. People often lost a lot of weight, were sometimes covered with Kaposi Sarcoma lesions, often couldn’t breathe because of the pneumonias’ that they had, and quite quickly people realized that if you got sick, you were going to die,” he continues.

5B, the unit on the hospital’s fifth floor, was created to try to provide aid and comfort. “The patients knew it was a death sentence; we knew it was and yet we tried to do what we could to help them stay comfortable as long as long as possible,” Volberding says. “So in the early years, it was mostly about trying to understand what was going on, starting to be able to predict a little bit about what was going to happen, and try to make it go a little bit more slowly.”

With its academic research environment, SF General became a kind of haven for the stricken.

“It was actually a popular place for gay men with AIDS to come because we were the only place that was doing actual research. The move to start the AIDS inpatient unit really came from the nurses who were seeing kind of spotty care around the hospital,” Volberding says. “It was to try to provide a place where these people really suffering and dying of AIDS would find a kind of loving environment. And the hospital absolutely went along with that right from Day One. They didn’t have to really be convinced. The community and the Health Department were so connected on this that it didn’t take a lot of effort – it certainly didn’t take any kind of activism to open up the unit.”

In 1985, the New York Times described 5B as “a model of care” for people with AIDS.

“Known within the hospital and the larger community as 5B, for its location on the fifth floor, the unit and its companion outpatient clinic, Ward 86, represent the unusual response by this city’s health care workers to acquired immune deficiency syndrome,” The Times reported. “For health care workers, 5B represents a victory over their own fears of the disease. It also forces them to focus on their feelings about homosexuality and their role in caring for a group of patients who will most surely die.”

Four years later, Los Angles still didn’t have a distinct AIDS Ward at LA County Hospital, prompting a series of demonstrations by ACT UP/LA.

“It was a shocking experience to watch people my own age dying in front of me,” Volberding says. “A lot of nurses were men and in a sense, they had it even worse because in many cases, they were gay themselves and some of them ended up having partners who died of AIDS. And some of them died of AIDS – not because they caught it at work but because they’re gay men.

I think the fact that women were very important part of the response is a significant one….They were true heroes. There’s no question about it.”

And unlike films such as “And The Band Played On…,” based on out San Francisco Chronicle reporter Randy Shilts’ book about the early days of AIDS, “5B” focuses on the unsung heroes and heroines of the crisis – the nurses.

Cliff Morrison created the unit and became the AIDS coordinator.

“I wasn’t the first person to talk about a specialized unit for the care of people with this disease,” Morrison told the Los Angeles Blade. “The first people to do so were those that wanted to get people with AIDS out of the general hospital population. They were saying that we had to separate, segregate and protect the ‘innocent.’ I was terrified and wanted nothing to do with.”

Morrison grew up in the rural South (the North Florida Panhandle on the Suwannee River) in the 1950s and a segregated unit “scared the hell out of me,” he says. However, keeping up with care for the burgeoning numbers of people with AIDS made him re-think his position.

“It was a constant struggle and battle with staff all over the hospital that wouldn’t perform the basic care needs for patients. Their rooms were not cleaned, beds not changed, food left outside their door, entering their rooms with all the isolation precautions and signage was horrifying. I began to think, what about a unit for all the right reasons,” Morrison says. “A place where patients could receive the level of care and compassion that they needed desperately and that they begging for. How about having staff, that are all professional nurses, that choose to be there, how about having a counseling staff for the caregivers, clients and their loved ones.”

In March 1983, Morrison discussed the idea with the Director of Nursing, including all the “challenges, obstacles, hysteria, backlash (from within the hospital and the outside community, locally and nationally),” and after coming up with a basic plan, the two started “quite a bit of convincing and cajoling” but, with the help of allies such as Mayor Dianne Feinstein and San Francisco Health Dept. Director Dr. Merv Silverman, the Chief of Medicine at SFGH, Dr. Merle Sande, got on board and “it was a go.”

That rural Southern experience, living with his poor, uneducated hard-working old half Native American grandmother growing up – a woman who became virtually a “personal servant” to the man who rescued her from farm work and poverty – had a profound impact on Morrison’s life. “I identified with her so much because I was the outsider in my family as well,” he says. “My grandmother used to hold me and rock me, telling me wonderful stories, and how much she loved me and that everything would be OK.”

As a teenager, Morrison gravitated to working in a hospital because he couldn’t handle working in the fields. “I hated dirty hands and always feeling gritty from dirt. Working as an orderly in the local county hospital, I was drawn to all people suffering but particularly the elderly, who were often alone. I found myself sitting with them, holding their hands, caressing them and hugging them,” he says, adding that he became the first in his family to graduate high school and go to college. At the time, there was a “great need for nurses” because of the Viet Nam War so he entered nursing.

“My need for the personal touch and touching others was an inherent part of me from a very early point in my development,” he says. “By the time I got to the situation at SFGH in 1982-83, I found myself going around the hospital coordinating their care on all the various units and it was clear what was really missing was human touch.

“There wasn’t a lot that I could do, but I could touch and hold them and I did,” Morrison says. “Much to the horror of other staff who criticized what I was doing, I realized that it was central to everything that we were trying, and should try, to do. When you touch someone in a loving, caring way, you share the most intimacy that you will ever share with another human being, and there is nothing sexual about it.”

Mary McGee was one of the many, many women who came forward to help the gay men society thought of as pariahs. Her first encounter with people with AIDS was in nursing school in New York. After graduating in 1984, she met others working on a medical surgical unit.

“They were all men and it was profound to see what they were going through and to see it in the context of knowing that there was just so much homophobia out there,” McGee tells the Los Angeles Blade, homophobia that combined with fear of the disease became “a vehicle for really marginalizing people.”

Straight and 22 with no previous connection to gays – though she had gone to a Catholic women’s college with a secret lesbian underground – she started having “some meaningful connections” with her patients. “I went down to Christopher Street in the Village for an AIDS vigil and people were sending candles out in little boats in the water, representing people who had died, and I was very deeply moved,” she says.

San Francisco beckoned McGee as a more manageable New York City. “And most importantly, I’d heard about this dedicated AIDS unit, which was the first in the country. And I was really, really hoping I could get a job there,” she says, which she eventually did.

As someone who was “really uncomfortable with the discrimination and the fear” against gay people, McGee focused on nursing as a response to suffering.

“The part about nursing that I loved was just really being present with people,” she says. “So that’s really what was being asked, just really be present with people and to touch them, to not be afraid to touch them and to hear their stories and meet their loved ones. And just to kind of counter this kind of ridiculous fear and homophobia. I don’t know how else to put it.”

McGee still sees numerous people’s faces” in front of her throughout her time nursing on 5A and 5B. But there is one gentleman she will never forget.

“He was in for PCP, but he’s responding to the treatment. He was a really sweet guy, articulate. He could still kind of walk on his own,” McGee recalls. “And there was another gentleman on the unit who had the terrible brain infection and his mental status was severely altered. He was agitated and he would yell out on the unit and you’d go in and try to soothe him and if you left he would start again. And I mean this poor guy…and the other man was very well aware of him.”

It’s the late 1980s. President Ronald Reagan had finally said the word “AIDS” and members of the presidential AIDS commission were coming to visit this model AIDS Ward. Everyone was nervous and the articulate AIDS patient reluctantly agreed to be the patients’ representative.

“I was on the night shift and he talked to me about it the night before it was going to happen,” McGee says. “And then I went home for the day to sleep, and I came back that evening and he told me that he had gotten a phone call that his mom had died. But he went ahead with the interview with the commission and shook the commissioner’s hand.

“And he’s telling me this story and the other patient is having a hard time,” McGee says. “And my patient who has gone through this that day — he’s walking the floors after what he’s been through. And he just went into that room and he sat with that man. He just sat him and comforted him. Well, it was, extraordinary. So that is someone that I will never forget. He is kind of a role model for me.”

Hank Plante, an openly gay reporter for the CBS News affiliate in San Francisco, is also featured in “5B.” He also notes the unheralded importance of women to the AIDS crisis.

“Some of the earliest caregivers for AIDS patients were lesbians and straight women. Many of the AIDS organizations in San Francisco were staffed and managed by these women. The public face of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation (the group’s Press spokesperson) was a lesbian, the group that delivered meals to people with AIDS (Project Open Hand) was founded by an elderly straight woman, the Shanti Project was run by a straight woman,” Plante tells the Los Angeles Blade. “So many gay men were overwhelmed taking care of themselves that it was a blessing to have these lesbians and straight allies helping them out.”

But while trained to be detached as as “objective” reporter, Plante could help but be impacted, too.

“As one of the first openly gay TV reporters in the country it was often hard for me to detach emotionally when covering AIDS stories” he says. “These were my brothers and sisters who were affected, so it was always more than just a story to me. There were many times when I was reporting at San Francisco General when I’d have to go out into the hallway and compose myself before going back into a patient’s room to finish an interview.

“I’m glad that by the time I got to San Francisco I had honed my skills enough so I could be a professional and get the job done, even though it was sometimes tearing me up inside,” Plante says.

“On the other hand, covering AIDS as a gay man working in the mainstream media was a way for me to channel my grief and my anger over the disease, and to make me feel like I was at least doing something to help,” PLante says. “I think many of us who survived those early years do have a form of PTSD today. You can’t lose that many friends without having it affect you for the rest of your life, as much we try to compartmentalize those years today. Being part of the film brought those walls down again, and from the audience reaction so far, I can tell other people are experiencing it all coming back as well.”

Volberding hopes the film will trigger thoughts of what we might do differently next time.

Next time?

“There will definitely be a next time,” Volberding says. “I think in a sense Ebola was a ‘next time.’ Zika was a ‘next time.’ It’s seeming that we’re seeing a whole series of new viruses appearing – nothing that approached HIV in terms of how frightening it is. But we didn’t expect HIV to come along, either.”

AIDS and HIV

Community is the cure: AIDS Walk LA returns to fight HIV and funding cuts

AIDS Walk Los Angeles returns to West Hollywood on October 12 with the theme ‘Community Is the Cure,’ highlighting the vital role of unity, radical community action, and advocacy in the fight against HIV/AIDS, stigma, and government funding cuts

APLA Health, a nonprofit providing HIV care, prevention, and sexual health services, announced the return of AIDS Walk Los Angeles on Sunday, October 12, 2025, starting from West Hollywood Park. This year’s theme, “Community Is the Cure,” emphasizes the role of unity in advancing progress against HIV/AIDS and supporting those affected.

Walk day will feature a live performance from RuPaul’s Drag Race star Heidi N Closet, DJ sets, and community booths. Following the celebration, walkers will make their way through the streets of West Hollywood.

“This event was born out of urgency, and it’s just as relevant today,” said Craig E. Thompson, CEO of APLA Health. “We’ve made incredible progress in the fight against HIV, but that progress is under direct threat from funding cuts and political attacks. Now is the time to show that we won’t be silenced or set back.”

Since its inception forty years ago, AIDS Walk Los Angeles has grown into one of the largest HIV/AIDS fundraising events in the world, raising nearly $100 million. Proceeds fund APLA Health’s services, including HIV specialty care, sexual health services, food and nutrition support, and housing assistance.

“The HIV/AIDS epidemic has always shown us that progress happens when people come together, when patients, neighbors, families, activists, and health providers stand shoulder to shoulder. Today, with funding under attack and stigma resurfacing, unity is not optional. ‘Community Is the Cure’ is a reminder that science alone isn’t enough. We need collective willpower, advocacy, and solidarity to ensure everyone has access to the care and dignity they deserve,” Thompson said.

Cuts to Medicaid, the Ryan White Program, and prevention funding threaten access to medications, housing assistance, and food security. “Here in Los Angeles, where tens of thousands rely on these programs, even modest reductions can push people back into crisis. AIDS Walk Los Angeles helps fill some of those gaps, but philanthropy cannot fully replace the government’s responsibility,” Thompson explained.

Communities of color, the medically underserved, people living in poverty, and those experiencing homelessness are disproportionately affected. “The barriers aren’t medical. They’re structural: stigma, lack of insurance, unstable housing, and underfunded safety-net services. The administration is underinvesting in the very programs designed to break down these barriers. Until that changes, inequities in HIV prevention and care will persist,” he said.

Funds raised by the walk provide housing, groceries, case management, and access to medical care. Thompson shared the story of one patient who had lost housing and had to choose between medication and meals. “Through AIDS Walk–funded programs, we were able to connect him to stable housing, consistent medical care, and our food pantry. Today, he is virally suppressed, working again, and mentoring others who are newly diagnosed with HIV. Stories like his are common, and they remind us that cuts aren’t just numbers on a spreadsheet, they’re setbacks in real people’s lives.”

Beyond fundraising, AIDS Walk LA is a platform for advocacy. “When thousands of people flood the streets of West Hollywood, it’s a visible reminder to our community that HIV/AIDS has not gone away and to policymakers that their decisions have life-or-death consequences. The walk puts pressure on elected officials to fund programs, fight stigma, and stand up for people affected by HIV,” Thompson said.

He urged the public to take action beyond walking and donating. “Call your elected officials. Demand that HIV services remain fully funded. Show up for community hearings. Support housing initiatives. Share facts on social media to counter stigma. And, importantly, talk. Without continued conversation about HIV/AIDS and sexual health, we jeopardize the incredible advancements we’ve made in HIV care and prevention.”

Thompson also framed the walk as part of a broader activist approach. “Radical action today means showing up for one another in tangible ways, housing someone, feeding someone, advocating for someone, and refusing to accept policies that erase people’s humanity. As our theme emphasizes, when politicians fail us, COMMUNITY IS THE CURE. For participants in AIDS Walk LA, it means recognizing that the walk is just the beginning. Each person can be a messenger, an advocate, and an ally in daily life. When we work together to get people connected to support services, the collective action is radical because it insists on care and dignity in a time when those values are under attack.”

“Activism ensures policymakers cannot quietly dismantle programs. Community solidarity means that no one gets left behind. Public pressure creates accountability. When thousands unite at AIDS Walk LA, it demonstrates the broad mandate to keep fighting until HIV is no longer a public health crisis. That unity is as important as any medical breakthrough,” Thompson concluded.

For more information on AIDS Walk Los Angeles and how to register, visit https://AIDSWALK.LA.

AIDS and HIV

“If not now, when?” Journalist and activist Karl Schmid is reshaping how we talk about HIV/AIDS

The Blade sits down with the award-winning host to talk about stigma and his latest initiative – taking HIV education onto the runway

Karl Schmid has long been a staple in queer news and media. Hailing from Australia, Schmid grew accustomed to the limelight from a young age, and eventually made a successful transition into American network television through his work on red carpets for ABC.

In 2018, he would be thrust into the spotlight for a different reason. Despite repeated warnings from professional acquaintances, Schmid came out as HIV positive to share his story, wear down stigmas, and to educate people about important and misunderstood science like the concept of undetectable equals untransmittable.

And so, Schmid would grow accustomed to renewal. In 2019, he launched Plus Life Media, a platform that shares HIV resources, education, and stories of resilience from people living with HIV/AIDS. He was part of the team behind the Emmy-nominated short documentary, Marty’s Place: Where Hope Lives: an intimate look into a housing cooperative created in the 1990s to support people with HIV/AIDS. Late last week, he flew to New York for the U.S. debut of his latest initiative: HIV Unwrapped. The project pairs researchers and scientists in HIV studies with fashion design students, culminating in a runway show that features bold reimaginings and interpretations of crucial science.

The Blade spoke with Karl about the cross-pollination in his own life and career, and how his latest effort is shaping the way he blends activism and media to reinvigorate conversations around HIV/AIDS.

HIV Unwrapped feels like a really interesting pivot into a different kind of modality and platform for you. Can you tell me more about the initiative and how it fits into your legacy of activism and work?

Well, HIV Unwrapped came out of Australia and this wonderful activist named Brent Allan, who I’m good friends with. And Brent had been at, I think, the WorldPride, or something that was happening in Australia, and there was an exhibition where they paired some engineers and science people of varying professions with a fashion designer to try and illustrate their work.

And he thought, “Wow, what a great way to maybe try and interpret HIV science and reignite the conversation around HIV.” So it started in Melbourne, Australia, and it was successful there. And then they did a version in the UK earlier this year. And then in July for the International AIDS Conference that took place in Kigali, in Rwanda, they did a version.

And that’s kind of where I stepped in. I think with HIV Unwrapped, you’re drawn into the fashion first — and then the science comes. It’s just a really unique and different way of reframing the conversation about HIV. But beyond that, it’s also working with fashion students, young people, and to see them become so invested in HIV science. That’s what gets me the most excited. Because you’re opening a whole new world to a person who doesn’t maybe really think about HIV all that much, and now they’ve learned all this amazing stuff. Suddenly you’ve got a whole new bunch of people talking about HIV in exciting and fresh ways, and they’re telling their friends and they’re having conversations about it.

You’re trying to create different entry points for people to not only talk about the science behind HIV and AIDS, but also how we can reinterpret it in original and visually interesting ways.

I mean, look, you’ve got the House Appropriations Committee willing to advance this “Big Beautiful Bill” that slashes $2 billion in HIV funding in this country, and as someone living with HIV, you keep going, “Why would they do that? Why? We are so close to ending HIV.” All of a sudden, we’ve stopped funding research, and we’re stopping this, and I’m just like, “Why?”

Now more than ever, we’ve got people and politicians and government and a large part of the United States who think, “Oh yeah, HIV isn’t a thing anymore. It’s not important.” Well, it is still a thing. It is still important, and HIV Unwrapped is a way to be creative and open new avenues of dialogue.

A friend of mine sent me a handwritten note the other day. This is in Texas. One of his roommates wrote a handwritten note to another roommate, saying, “Oh, just so you know, ‘such and such’ has AIDS. So I’d be scrubbing the shower if I were you after he uses it. I personally have decided to go and shower at the gym.” And this is a person in their 30s, so we’re still having these dumb conversations from 1984.

That’s why I do what I do with Plus Life, and that’s why I’m like, “Wow, HIV Unwrapped is another tool in our toolbox we can use.” And I guess our hope is really that scientists will see this across the country and around the world and go, “Well, that is a really cool way to explain my science and make it accessible,” and want to engage in future projects like this.

How queer communities are represented in the media can leave deep imprints. I was watching an older interview you did where you recall this HIV ad you saw in a movie theater as a kid. The Grim Reaper’s there, and it’s creepy and sinister. It seems like we’ve moved away from that kind of imagery — but it doesn’t feel like we’ve necessarily come to a much better understanding of HIV/AIDS. Where do you think we’re at now in terms of representation?

The fact that, to this day, I can tell you where I was, what the movie was, that it was a Saturday, which cinema it was in, and I was a seven year old kid. It gives you an idea of how burned into my memory that is. And, I agree. I think we’ve moved away largely from the fear tactics, but we’ve stopped talking about it. I’d like to think that we’ve gotten better in representing people living with HIV, on television and film, as just people living with HIV. Where HIV doesn’t become the central storyline, and it’s not a doom and gloom, “woe is me” story. It’s just part of who they are.

But we sort of dance around anything that’s to do with our bodies or sex or sexuality, because it makes us uncomfortable. And so when I pitch stories to ABC and other networks, and even, quite frankly, trying to get press to cover HIV Unwrapped: we get passed on. People don’t want to talk to us because HIV isn’t sexy. As long as we keep doing that and having that reaction — if we don’t talk about it — we don’t get to a place where we can be comfortable with it.

Since I came out about my status all those years ago, my focus has been trying to normalize the conversation. That’s how we grow, and that’s how we learn — whether it’s HIV, whether it’s politics, whether it’s anything. But if we don’t talk about it, and we sort of pretend it doesn’t exist, and then we cut funding for it, and we sort of sweep it under the rug: it ain’t going to go anywhere.

Women of color, Black and brown women, have the highest infection rates in the United States. In the south those rates keep going up and up and up, and now we’re cutting funding to testing and to counseling and to services. I’m really worried that we will end up back with AIDS wards in hospitals again, and there’s no need for it.

To bring it back to HIV Unwrapped, that’s why, if I can come up and work with an amazing group of people to tell stories and to have conversations in fresh ways, then I’m going to keep doing it — whether it’s HIV Unwrapped, whether it’s what I do on Plus Life, whether it’s a television show or whatever crazy thing I come up with next.

It feels like there’s so much watering-down in terms of conversations around sexual health, HIV and AIDS. What is the resistance that you’ve faced, and how has that resistance changed over the years?

I’ve heard, “I think what you’re doing is great. It’s just not the right time to tell the story.” Well, when is the right time to tell the story? I think so many people in America think HIV doesn’t affect them. And the reality is very different. HIV affects everybody. If not now, when? People are still dying in this country. People are afraid to get tested, and they’re living in shame. And they’re hiding what’s wrong with them because of the stigma — and that just shouldn’t be happening.

I’ve said this a million times too. You know, HIV and AIDS doesn’t kill you. That’s not what’s going to put me in the grave. But it’s the stigma. It’s the bigoted, out-of-date opinions of Congress and politicians and public figures and uneducated people who just think this is somehow some deviant, dirty “sex disease” or drug disease, and those of us who get it deserve it. And you know, television networks, especially, are in the business of making money. And to do that, they sell advertising, and so they’re worried that advertisers will turn off if you talk about this kind of stuff.

And I think it’s maybe a little bit the opposite. I think if you can find, again, engaging and interesting ways to have real conversations, I’ve certainly found that you get a very vast and wide audience of people who will chime in and may have an opinion. And again, our opinions may differ, and that’s okay, but, but as long as we’re having the conversation, the more you say it, the less scary it is.

Almost 20 years after you were first diagnosed with HIV, do you see yourself pivoting now to work more on activism? Is that something you’re trying to focus more on now at this point of your career?

I will say that I’m incredibly fortunate to have worked for as many years as I have in broadcast, and I’ve done some really amazing things, and had some phenomenal opportunities going to the Oscars and doing all those red carpets and celebrity interviews all over the world. They’re all valuable experiences that I’ve been able to build upon. But I will say that in the last sort of two years, especially, my focus has become more about Plus Life and doing these kinds of stories and these kinds of initiatives.

I am fascinated by people. I think to be a decent journalist or broadcaster, you have to have that innate curiosity. And I am deeply curious about people and people’s behavior and where they come from, and what kind of homes they grew up in, what their friends are like. It’s incredibly satisfying to me. Do I miss being on regular, scheduled programming and television? Sure. It was a fantastic platform, and there’s nothing quite like the thrill of live television for me, and that’s why I loved being in news and entertainment news.

I think as I sort of get older, and I’m no longer the young kid on the block, and I’m not so nimble with my thumbs and my forefingers when it comes to putting stuff up on social media and Tik Tok and all of that…If I’ve got an opportunity to really hone in on the stuff that I do with Plus Life, there’s nothing more rewarding than that, right?

A behind-the-scenes documentary of the U.S. debut of HIV Unwrapped will be available to stream on November 30th, just before World AIDS Day.

AIDS and HIV

Assemblymembers urge Governor Newsom to sign “lifeline” bill for HIV medication

AB 554 amends existing law that restricts access to PrEP medication

On September 10, Assembly Bill (AB) 554, or the PrEPARE Act (Protecting Rights, Expanding Prevention, and Advancing Reimbursement for Equity Act), was passed with a majority vote by the California State Assembly and Senate. Today, the bill’s leaders are urging Governor Newsom to sign it into law.

“With a powerful coalition behind AB 554, we were able to get this bill through the process swiftly, and are hopeful that the Governor will see the need for the LGBTQ+ community,” Los Angeles Assemblymember Mark Gonzalez, one of the bill’s co-authors, told the Blade.

AB 554 was first introduced in February, and was penned by Assemblymember Gonzalez and San Francisco Assemblymember Matt Haney. It was formed to amend existing laws around health insurance coverage that currently restrict access to certain antiretroviral drugs, or HIV preventative medicine like PrEP and PEP, and to ease difficulties community clinics face in administering these medications and receiving reimbursement. The bill will also require health care plans to cover FDA-approved HIV medication without enforcing prior authorization or step therapy.

For Gonzales and the bill’s supporters, AB 554 is about boosting access to various forms of effective HIV preventative medicine and providing a safeguard for people as the state of HIV research and treatment enters unsteady ground. This all comes in the midst of the debate around the House Committee on Appropriations’s 2026 Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies funding bill, which proposes $1.7 billion in cuts to domestic HIV prevention and research efforts, as well as programs that provide care for people living with HIV/AIDS — particularly, low-income people of color.

Assemblymember Gonzalez stated to the Blade that this is a “stark reminder that this epidemic still hits our communities of color the hardest,” and wants to address this by evolving and updating laws to reflect local needs. He is hopeful about the Governor’s impending response, and stated that the bill is “not just a policy; it is a lifeline.”

“It’s about giving people real choices, equipping small clinics with the tools they need to protect lives,” Gonzalez continued, “and ensuring that California continues to put public health over politics.”

AIDS and HIV

Local organization aims to support and assist Black LGBTQ+ community

REACH LA is stepping up their mission amid hostile administration

REACH LA, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit organization aimed at working with youth of color, is stepping up their prevention resources during Black History Month to support the LGBTQ+ community of color.

Though today is National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, REACH LA works year-round to provide resources to their community members.

This month, the organization is amplifying its mission to support Black LGBTQ+ youth by offering free HIV testing and care throughout February, offering a $25 gift card as incentive to get tested. This and all of REACH LA’s efforts are geared toward assisting the marginalized Black and Latin American communities by reducing stigma, increasing education and assisting community members with resources.

The QTBIPOC community is especially vulnerable to political and personal attacks. As we head into the next four years under a hostile administration whose goal is to erase queer and trans people, there will be continued attacks on federal funding and on any other front possible.

“This year, it is especially vital, more than ever, to amplify and commemorate National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. At REACH LA, we are currently engaging with individuals and partnerships while navigating through dire and uncertain times where HIV/AIDS awareness prevention efforts, access, and visibility have been under attack and restricted,” said Jeremiah Givens, chief marketing and communications officer at REACH LA.

It is important to spotlight the intersection between health equity, Black LGBTQ+ empowerment and community-based solutions during Black History Month and every other month throughout the year and especially during this particularly vulnerable time.

As one of eight CDC PACT Program Partners, REACH LA celebrates National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day with a Positive Living Campaign in collaboration with the CDC’s Let’s Stop HIV Together initiative. The campaign highlights the resilience of individuals living with HIV and works to raise awareness and foster community support.

To learn more about resources, visit their website or stop in for testing, support and other resources. The organization’s doors are open Monday through Friday, from 11 AM to 7 PM for free, on-site HIV testing and assistance with accessing PREP and PEP, linkage to care and free mental health therapy.

Over 300 people gathered last Monday to commemorate World AIDS Day in an event hosted by Bienestar Human Services. The non-profit focuses on identifying and addressing emerging health issues faced by Latinx and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans Queer and more (LGBTQ+) populations.

The main objective of the annual event was to light a candle to honor those who passed away due to Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and celebrate those who, despite the condition, keep going.

HIV is the virus that causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Once you have HIV, the virus stays in the body for life, and while there is no cure. There is, however, medicine that can help people stay healthy, states Planned Parenthood. HIV destroys the cells that protect the human body from infections. If a person doesn’t have enough of these CD4 or T cells, the body can’t fight off infections as normal. This damage can lead to AIDS, which is the most serious stage of HIV, and it leads to death over time.

In the U.S., there are about 1.3 million people newly infected with HIV in 2023 and 39.9 million living with HIV, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

Living with HIV for decades

Among the participants at the event at the Ukrainian Culture Center on Melrose in East Hollywood was Marcela, a transgender woman who was diagnosed HIV positive 33 years ago. She said when she learned about her diagnosis, she was so depressed she tried to commit suicide. She ended up at the hospital, and after getting better, she heard about an organization that was helping people with health issues such as hers.

“Since then, I learned to live with this condition because it is not an illness; it’s a condition,” she said.

Bienestar celebrated the World AIDS Day on December 2, 2024. (Courtesy of Bienestar)

Marcela, who didn’t provide her last name, said she not only found a new way of living with HIV but also found an extended family at Bienestar. They have guided her on how to receive the proper treatment and medicines, to be part of a support group and even to pay her rent when she needed it the most.

The 64-year-old woman doesn’t have any family members in the United States. She said five years ago, her husband passed away of pneumonia. She was living alone in Long Beach and got behind her payments during the pandemic. She said Bienestar helped her apply for a grant of over $20,000 that secured the payment for her rent, and now she is debt-free.

“I’m extremely grateful to them and all the help they provide,” she said.

Working for the community

This year, Bienestar is celebrating 35 years of serving the LGBTQ+ community. Among the many programs they offer is the Support Group for Transgender Women, which Marcela belongs to.

Mia Perez, the support group manager, said 15 to 20 members attend the group every Friday from 3 to 5 p.m. They talk about their feelings, share experiences, and plan and participate in social events.

Perez said one of the participants’ biggest concerns is accepting reality once they have been diagnosed. “However, with all these new treatments people that are HIV positive can have a normal relationship with someone who doesn’t have HIV. It’s all about getting informed,” said Perez.

Other concerns include what will happen to them once the new presidential administration takes office since they have plans to deport immigrants and many of the transgender women are immigrants.

“That’s why we are trying to get in contact with an immigration attorney or an organization so they can keep them informed of their rights,” said Perez.

Bienestar events, like World AIDS Day, help those affected create a stronger community, and they realize the recognition is not just for those who are HIV positive but also for their families and friends.

Marcela said when she is feeling down or bored at home, all she has to do is go to Bienestar and the people there always give her a warm welcome.

“They give me coffee, they offer me lunch. Being there is like being at home,” she said.

AIDS and HIV

New monument in West Hollywood will honor lives lost to AIDS

In 1985, WeHo sponsored one of the first awareness campaigns in the country, nationally and globally becoming a model city for the response to the epidemic

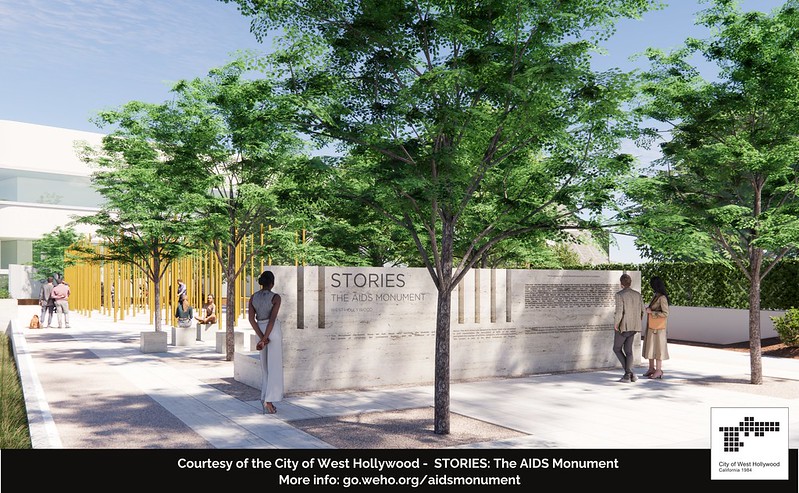

December is AIDS/HIV awareness month and this year West Hollywood is honoring the lives lost, by breaking ground on a project in West Hollywood Park that has been in the works since 2012.

Members of Hollywood’s City Council joined representatives from the Foundation of AIDS Monument to announce the commencement of the construction of STORIES: The AIDS Monument, which will memorialize 32 million lives lost. This monument, created by artist Daniel Tobin, will represent the rich history of Los Angeles where many of those afflicted with HIV/AIDS lived out their final days in support of their community.

Tobin is a co-founder and creative director of Urban Art Projects, which creates public art programs that humanize cities by embedding creativity into local communities.

The motto for the monument is posted on the website announcing the project.

“The AIDS Monument:

REMEMBERS those we lost, those who survived, the protests and vigils, the caregivers.

CELEBRATES those who step up when others step away.

EDUCATES future generations through lessons learned.”

The monument will feature a plaza with a donor wall, vertical bronze ‘traces’ with narrative text, integrated lighting resembling a candlelight vigil, and a podium facing North San Vicente Blvd.

World AIDS Day, which just passed, is on December 1st since the World Health Organization declared it an international day for global health in 1988 to honor the lives lost to HIV/AIDS.

The Foundation for the AIDS monument aims to chronicle the epidemic to be preserved for younger generations to learn the history and memorialize the voices that arose during this time.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic particularly affected people in Hollywood during the onset of the epidemic in the 1980s. The epidemic caused a devastatingly high number of deaths in the city. The city then became one of the first government entities to provide social service grants to local AIDS and HIV organizations.

In 1985, the city sponsored one of the first awareness campaigns in the country, nationally and globally becoming a model city for the response to the epidemic.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released the theme for World AIDS Day, ‘Collective Action: Sustain and Accelerate HIV Progress.’

The city of West Hollywood continues to strive to become a HIV Zero city with its current implementation of HIV Zero Initiative. The initiative embraces a vision to “Get to Zero” on many fronts: zero new infections, zero progression of HIV to AIDS, zero discrimination and zero stigma.

Along with the initiative and the new AIDS monument, the city also provides ongoing support and programming through events for World AIDS Day and the annual AIDS Memorial Walk in partnership with the Alliance for Housing and Healing.

For more information, please visit www.weho.org/services/human-services/hiv-aids-resources.

AIDS and HIV

National Latino AIDS Awareness Day: Breaking down stigma, silence and silos

FLAS provides HIV and STD education

When Elia Chino, Founder and Executive Director of the Fundacion Latinoamericana De Acción Social (FLAS) Inc., initially approached major HIV/AIDS agencies in Houston, Texas for support in starting an organization tailored specifically to reaching Latino populations, she was met with confusion.

“Why do you want to start a separate organization?” they asked. “We’re here!”

Chino remembers her frustration. “They didn’t understand,” she said. “Our brothers and sisters were dying, and the community needed services that they couldn’t provide.”

Indeed, in the 1990s, barriers to HIV care and treatment for Latino populations were markedly different from those faced by other populations. Information about the HIV epidemic was largely in English, and inaccessible to many individuals who had immigrated from indigenous Latin American communities and never learned to read and write in their native language, let alone English. When they were able to access treatment, Latino individuals often faced mistreatment at primary care facilities due to a lack of culturally competent care.

Perhaps most challenging was the culture of silence. Many Latino immigrants living with HIV in the United States fled homophobia, transphobia and stigma in their home countries, and were still grappling with lasting shame and guilt. Despite many people dying, there was little open discussion or education about the cause. In fact, Chino didn’t even know that the HIV epidemic took the lives of some of her best friends until speaking with their families years later.

“No one was talking about their diagnosis,” says Chino. “People had come to the United States for freedom, but still weren’t ready to talk about who they were. There was a real atmosphere of stigma, taboo, misinformation and fear.”

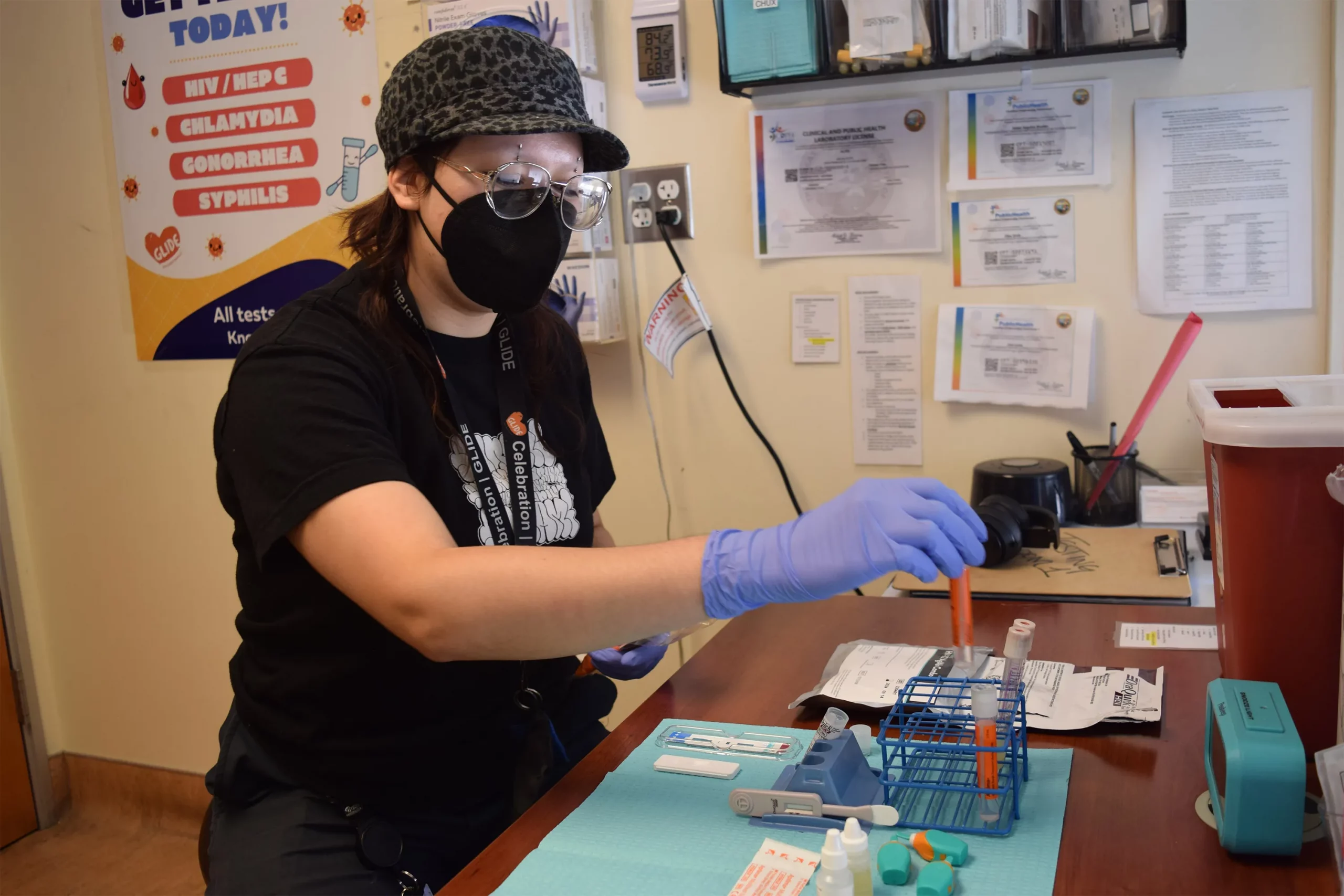

At the time, Chino was volunteering at a hospital serving communities without insurance. The fourth, fifth and sixth floors were all dedicated to treating people with HIV. Chino began educating herself on this crisis while she volunteered at the hospital, and founded FLAS in 1994 after discovering that the majority of HIV prevention efforts were not reaching Latino individuals.

In the beginning, without support from other organizations in the area or resources to expand, Chino was a one-woman show, conducting outreach in clubs, cantinas and bars by herself. She hadn’t anticipated the barriers she’d face as a member of the LGBTQ+ community and an immigrant. Horrible discrimination, a language barrier and intense HIV stigma in the communities she was working in made the work challenging, but also emphasized the necessity of what she was doing.

Over time, with support and funding from organizations like Gilead Sciences, FLAS has been able to expand its services from solely HIV prevention to include HIV testing, behavioral health services, housing and social services assistance, support groups and a food pantry. The organization has started hosting educational events everywhere from churches to street corners, raising awareness about HIV in the Houston community. Chino also started collaborating with the consulate of Mexico to help newcomers navigate U.S. health systems and services when they arrive in the United States. Next year, the organization will start offering mobile HIV testing clinics for communities in need.

Since its launch, FLAS has been able to expand its initial focus to address the holistic drivers of this crisis, moving beyond medical determinants of health to tackle the social and structural barriers that perpetuate the HIV epidemic and prevent Latino populations from accessing comprehensive treatment.

“Everyone keeps telling Latino individuals to get tested, but this does nothing unless you actually incentivize people to do so,” says Chino. “People have to go to work. They have to pay their rent. They have to buy food. Many can’t afford to lose their salary and spend a full day coming in to do a test or get treatment. We have to make it easier to access HIV prevention and treatment, and we have to provide incentives.”

This year marked FLAS’s 30th anniversary, which the organization celebrated with a gala in August. They have made a huge impact in Houston since their launch – providing HIV and STD education to over 500,000 Latino people, distributing over 20,000 HIV tests, referring over 40,000 people for social services and hosting over 6,000 educational events and health fairs in English and Spanish. However, many of the challenges for HIV prevention and treatment for Latino populations remain.

“We have over 30,000 individuals living with HIV in Houston, yet when we ask for people to talk about their status, no one comes forward to tell their stories. HIV is a chronic disease, but stigmatization is still so strong in the Latino community,” says Chino. “You can say you have cancer, high blood pressure, diabetes, whatever – but nobody says I have HIV. There is still so much work to do.”

As a testament to their important programming, FLAS is a recipient of funding through Gilead Sciences’ TRANScend® Community Impact Fund, a program aimed at empowering Trans-led organizations working to improve the safety, health and wellness of the Transgender community. Since its inception in 2019, TRANScend has awarded more than $9.2 million in grants to 26 community organizations across 15 U.S. states and territories.

TRANScend support has been critical to helping FLAS maintain its services. In 2020, in the midst of the COVID pandemic, Gilead’s funding helped FLAS continue to offer virtual behavioral and mental health services to the community when their physical offices had to close.

According to Chino, this type of partnership is critical to ending the HIV epidemic in Latino communities, especially for meeting communities where they are.

“Communities trust their grassroots organizations, and grassroots organizations provide for their communities,” she says. “At the end of the day, we need to continue to support the groups doing the difficult work on the ground with the people they’re serving, especially those breaking down stigma and lasting barriers to care for Latino communities.”

AIDS and HIV

40th anniversary AIDS Walk happening this weekend in West Hollywood

AIDS Project Los Angeles Health will gather in West Hollywood Park to kick off 40th anniversary celebration

APLA Health will celebrate its 40th anniversary this Sunday at West Hollywood Park, by kicking off the world’s first and oldest AIDS walk with a special appearance by Salina Estitties, live entertainment, and speeches.

APLA Health, which was formerly known as AIDS Project Los Angeles, serves the underserved LGBTQ+ communities of Los Angeles by providing them with resources.

“We are steadfast in our efforts to end the HIV epidemic in our lifetime. Through the use of tools like PrEP and PEP, the science of ‘undetectable equals intransmissible,’ and our working to ensure broad access to LGTBQ+ empowering healthcare, we can make a real step forward in the fight to end this disease,” said APLA Health’s chief executive officer, Craig E. Thompson.

For 40 years, APLA Health has spearheaded programs, facilitated healthcare check-ups and provided other essential services to nearly 20,000 members of the LGBTQ+ community annually in Los Angeles, regardless of their ability to pay.

APLA Health provides LGBTQ+ primary care, dental care, behavioral healthcare, HIV specialty care, and other support services for housing and nutritional needs.

The AIDS Walk will begin at 10AM and registrations are open for teams and solo walkers. More information can be found on the APLA Health’s website.

AIDS and HIV

Cautious Optimism in San Francisco as New Cases of HIV in Latinos Decrease

The decrease could mark the first time in five years that Latinos haven’t accounted for the largest number of new cases

SAN FRANCISCO — For years, Latinos represented the biggest share of new HIV cases in this city, but testing data suggests the tide may be turning.

The number of Latinos newly testing positive for HIV dropped 46% from 2022 to 2023, according to a preliminary report released in July by the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

The decrease could mark the first time in five years that Latinos haven’t accounted for the largest number of new cases, leading to cautious optimism that the millions of dollars the city has spent to remedy the troubling disparity is working. But outreach workers and health care providers say that work still needs to be done to prevent, and to test, for HIV, especially among new immigrants.

“I am very hopeful, but that doesn’t mean that we’re going to let up in any way on our efforts,” said Stephanie Cohen, who is the medical director of the city’s HIV and STI prevention division.

Public health experts said the city’s latest report could be encouraging, but that more data is needed to know whether San Francisco has addressed inequities in its HIV services. For instance, it’s still unclear how many Latinos were tested or if the number of Latinos exposed to the virus had also fallen — key health metrics the public health department declined to provide to KFF Health News. Testing rates are also below pre-pandemic levels, according to the city.

“If there are fewer Latinos being reached by testing efforts despite a need, that points to a serious challenge to addressing HIV,” said Lindsey Dawson, the associate director of HIV Policy and director of LGBTQ Health Policy at KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

San Francisco, like the rest of the country, suffers major disparities in diagnosis rates for Latinos and people of color. Outreach workers say that recent immigrants are more vulnerable to infectious diseases because they don’t know where to get tested or have a hard time navigating the health care system.

In 2022, Latinos represented 44% of new HIV cases in San Francisco, even though they accounted for only 15% of the population. Latinos’ share of new cases fell to 30% last year, while whites accounted for the largest share of new cases at 36%, according to the new report.

Cohen acknowledged a one-year decline is not enough to draw a trend, but she said targeted funding to community-based organizations may have helped lower HIV cases among Latinos. A final report is expected in the fall.

Most cities primarily depend on federal dollars to pay for HIV services, but San Francisco has an ambitious target to be the first U.S. city to eliminate HIV, and roughly half of its $44 million HIV/AIDS budget last year came from city coffers. By comparison, New Orleans, which has similar HIV rates, kicked in only $22,000 of its $13 million overall HIV/AIDS budget, according to that city’s health department.

As part of an effort to address HIV disparities among LGBTQ+ communities and people of color, San Francisco last year gave $2.1 million to three nonprofits — Instituto Familiar de la Raza, Mission Neighborhood Health Center, and San Francisco AIDS Foundation — to bolster outreach, testing, and treatment among Latinos, according to the city’s 2023 budget.

At Instituto Familiar de la Raza, which administers the contract, the funding has helped pay for HIV testing, prevention, treatment, outreach events, counseling, and immigration legal services, said Claudia Cabrera-Lara, director of the HIV program at Sí a la Vida. But ongoing funding isn’t guaranteed.

“We live with the anxiety of not knowing what is going to happen,” she said.

The public health department has commissioned a $150,000 project with Instituto Familiar de la Raza to determine how Latinos are contracting HIV, who is most at risk, and what health gaps remain. The results are expected in September.

“It could help us shape, pivot, and grow our programs in a way that makes them as effective as possible,” Cohen said.

The center of the HIV epidemic in the mid-1980s, San Francisco set a national model for response to the disease after building a network of HIV services for residents to get free or low-cost HIV testing, as well as treatment, regardless of health insurance or immigration status.

Although city testing data showed that new cases among Latinos declined last year, outreach workers are seeing the opposite. They say they are encountering more Latinos diagnosed with HIV while they struggle to get out information about testing and prevention — such as taking preventive medications like PrEP — especially among the young and gay immigrant communities.

San Francisco’s 2022 epidemiological data shows that 95 of the 213 people diagnosed at an advanced stage of the virus were foreign-born. And the diagnosis rate among Latino men was four times as high as the rate for white men, and 1.2 times that of Black men.

“It’s a tragedy,” said Carina Marquez, associate professor of medicine in the Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases, and Global Medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, the city’s largest provider of HIV care. “We have such great tools to prevent HIV and to treat HIV, but we are seeing this big disparity.”

Because Latinos are the ethnicity least likely to receive care in San Francisco, outreach workers want the city to increase funding to continue to reduce HIV disparities.

The San Francisco AIDS Foundation, for instance, would like more bilingual sexual health outreach workers; it currently has four, to cover areas where Latinos have recently settled, said Jorge Zepeda, its director of Latine Health Services.

At Mission Neighborhood Health Center, which runs Clinica Esperanza, one of the largest providers of HIV care to Latinos and immigrants, the number of patients seeking treatment has jumped from about two a month to around 16 a month.

Among the challenges is getting patients connected to mental health and substance abuse bilingual services crucial to retaining them in HIV care, said Luis Carlos Ruiz Perez, the clinic’s HIV medical case manager. The clinic wants to advertise its testing and treatment services more but lacks the money.

“A lot of people don’t know what resources are available. Period,” said Liz Oates, a health systems navigator from Glide Foundation, who works on HIV prevention and testing. “So where do you start when nobody’s engaging you?”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

AIDS and HIV

White House urged to expand PrEP coverage for injectable form

HIV/AIDS service organizations made call on Wednesday

A coalition of 63 organizations dedicated to ending HIV called on the Biden-Harris administration on Wednesday to require insurers to cover long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) without cost-sharing.

In a letter to Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the groups emphasized the need for broad and equitable access to PrEP free of insurance barriers.

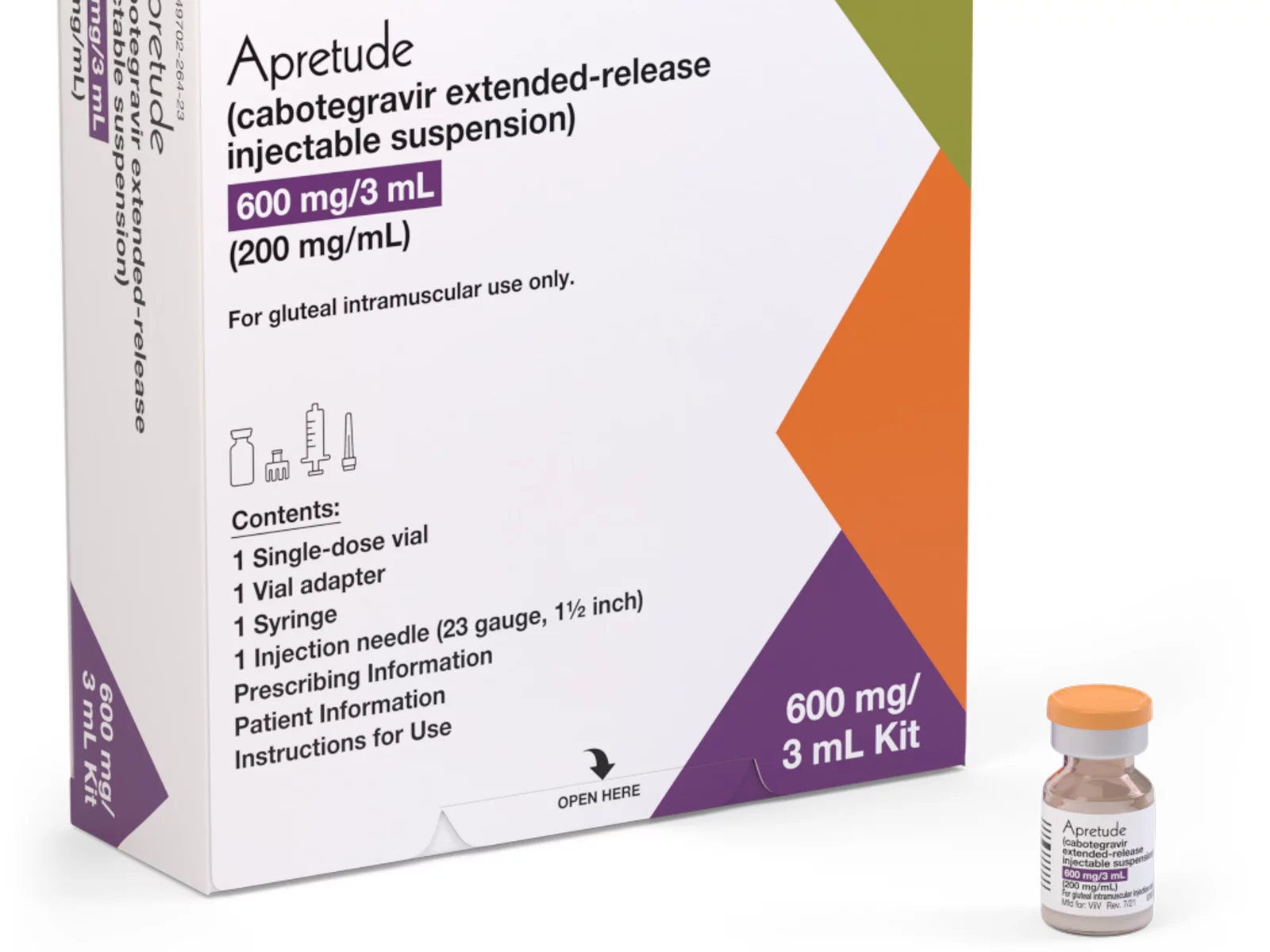

Long-acting PrEP is an injectable form of PrEP that’s effective over a long period of time. The FDA approved Apretude (cabotegravir extended-release injectable suspension) as the first and only long-acting injectable PrEP in late 2021. It’s intended for adults and adolescents weighing at least 77 lbs. who are at risk for HIV through sex.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendation for PrEP on Aug. 22, 2023, to include new medications such as the first long-acting PrEP drug. The coalition wants CMS to issue guidance requiring insurers to cover all forms of PrEP, including current and future FDA-approved drugs.

“Long-acting PrEP can be the answer to low PrEP uptake, particularly in communities not using PrEP today,” said Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute. “The Biden administration has an opportunity to ensure that people with private insurance can access PrEP now and into the future, free of any cost-sharing, with properly worded guidance to insurers.”

Currently, only 36 percent of those who could benefit from PrEP are using it. Significant disparities exist among racial and ethnic groups. Black people constitute 39 percent of new HIV diagnoses but only 14 percent of PrEP users, while Latinos represent 31 percent of new diagnoses but only 18 percent of PrEP users. In contrast, white people represent 24 percent of HIV diagnoses but 64 percent of PrEP users.

The groups also want CMS to prohibit insurers from employing prior authorization for PrEP, citing it as a significant barrier to access. Several states, including New York and California, already prohibit prior authorization for PrEP.

Modeling conducted for HIV+Hep, based on clinical trials of a once every 2-month injection, suggests that 87 percent more HIV cases would be averted compared to daily oral PrEP, with $4.25 billion in averted healthcare costs over 10 years.

Despite guidance issued to insurers in July 2021, PrEP users continue to report being charged cost-sharing for both the drug and ancillary services. A recent review of claims data found that 36 percent of PrEP users were charged for their drugs, and even 31 percent of those using generic PrEP faced cost-sharing.

The coalition’s letter follows a more detailed communication sent by HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute to the Biden administration on July 2.

Signatories to the community letter include Advocates for Youth, AIDS United, Equality California, Fenway Health, Human Rights Campaign, and the National Coalition of STD Directors, among others.

-

Riverside County4 days ago

Riverside County4 days agoYesterday, Palm Desert residents shut down Councilmember’s “hateful” proposal to remove City’s Pride Month resolution

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoLA County contributes over $181K to Out Athlete Fund for Pride House LA/West Hollywood

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoAs house Democrats release Epstein photos, Garcia continues to demand DOJ transparency

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoLGBTQ Democrats say they’re ready to fight to win in 2026

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoWhite House deadnames highest-ranking transgender official

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoGeorge Santos speaks out on prison, Trump pardon, and more

-

Books2 days ago

Books2 days ago‘Dogs of Venice’ looks at love lost and rediscovered

-

Crime & Justice3 days ago

Crime & Justice3 days agoSan Fernando Valley LGBTQ+ community center Somos Familia Valle is trying to rebuild from a “traumatizing” break-in

-

a&e features9 hours ago

a&e features9 hours agoAllison Reese’s advice? Take your comedic medicine.