Features

Seeding a gay community in LA, the gay liberation revolution

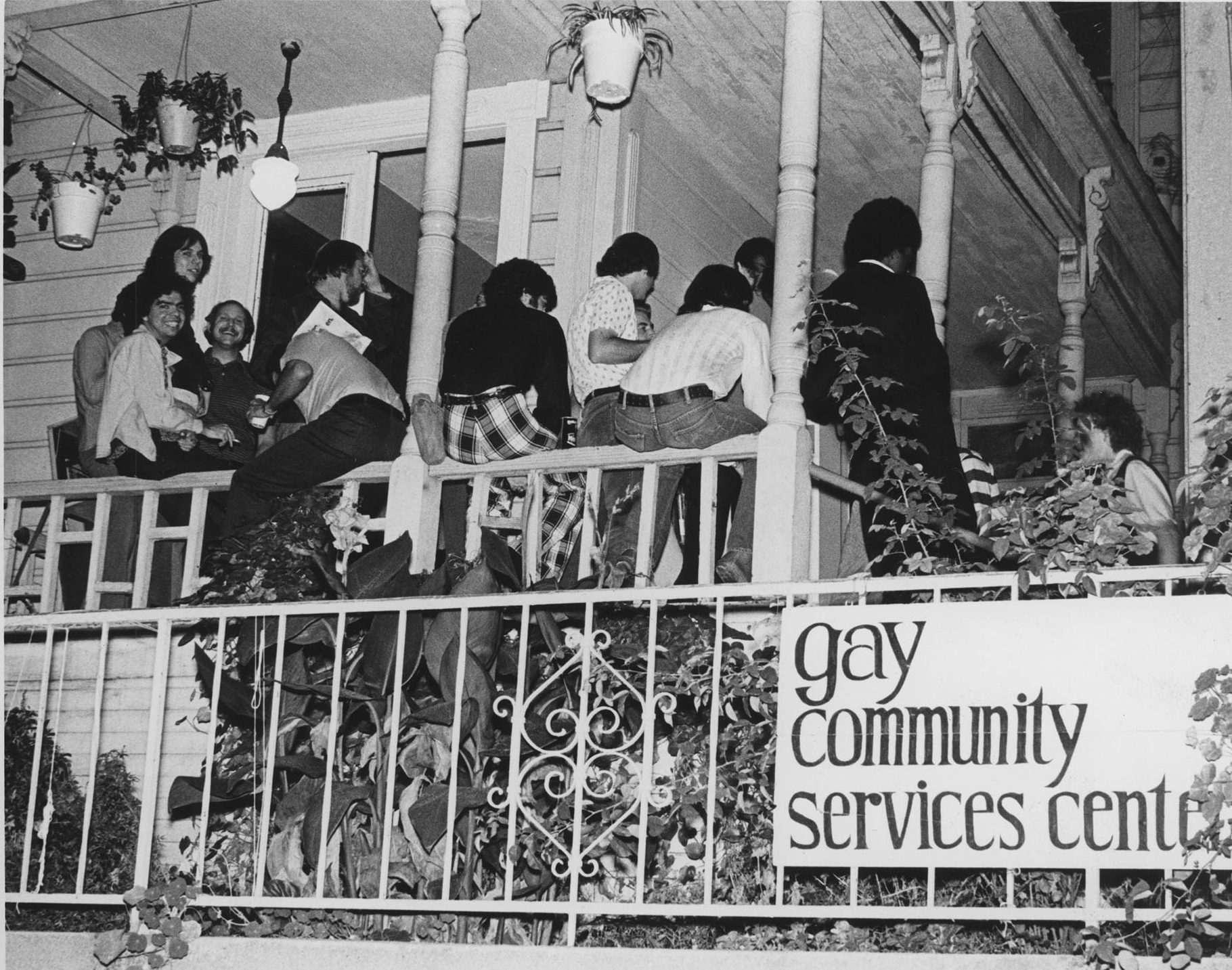

1970 was an incredible year of achievement for GLF in LA. Marches, protests, & a broad range of other militant, highly visible actions

By Don Kilhefner | LOS ANGELES – There is a big difference in magnitude between a liberation movement and a civil rights movement. Often, the terms “Gay Liberation” and “Gay Civil Rights” are used synonymously. Those terms, however, are very different in meaning.

A liberation movement involves an oppressed group seizing power by its own militant efforts and includes a change in consciousness by an oppressed people about its alleged inferiority, restructures economic and educational systems, and claims or reclaims the group’s history and culture. The central organizing principle of a civil rights movement is lobbying the dominant power structure over time to grant new laws—like voting rights—which gives more equal rights to a minority or majority historically discriminated against without any fundamental changes or threats to the power, economic, or educational systems in place.

Power structures try to destroy liberation movements, as in South Africa in 1961 when Nelson Mandela and others created the paramilitary Spear of the Nation, turning the African National Congress from a civil rights movement into a liberation movement. On the other hand, civil rights movements are easily pacified by political posturing and pretending and assimilated by elite capture without posing much of a threat to the basic power structures of society. Liberation movements are also susceptible to elite capture.

Author’s Note You are advised to remember as you read the following article that all of the Gay Liberation organizing being described was done within a context of 1,000 years or more of hetero supremacy in the West in which all religions declared lesbians and particularly gay men to be subhuman and an abomination in the eyes of God; all national and local laws declared them to be illegal and a crime against nature, with police and vigilante groups hunting them down and killing such deviants, often burning them alive at the stake; and in the 20th century the new science of psychology declared them a severe psychopathology and a threat to society. Gay men and lesbians internalized that hetero supremacist, genocidal ideology, turning it into self-hate, and turning that debasement into fear of being found out, some in fear for their very lives. And so, in 1969, still being officially labeled sick, sinful, and against the law and against the laws of nature, a new, revolutionary narrative unfolded in Los Angeles.

Central to the development of a radical, militant Gay Liberation revolution in Los Angeles was the L.A. Gay Liberation Front, which was called into being in August 1969 by Morris Kight, an anti-Vietnam War activist. GLFs were also organized in other major U.S. cities in the aftermath of the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion, a single spark that caused a prairie fire. A gay revolution ensued—a revolution defined as “sudden, radical, complete change.”

For months, GLF meetings were held every Sunday afternoon in random, obscure locations, until, on January 1, 1970, I secured a GLF office at 577 ½ North Vermont Ave. in East Hollywood, formerly occupied by the Hollywood contingent of the Peace and Freedom Party. Using basic organizing skills learned as a volunteer at the Peace and Freedom Party office in Venice while a UCLA doctoral student in history, I became GLF’s around-the-clock, sleep-in office manager, creating a GLF infrastructure for the first time, including a telephone number, mailing address, bank account, and a stable meeting and organizing space.

The office was located on the second floor of a graceful dowager of a fourplex next to the Hollywood Freeway. Soon after GLF left the space, the building was demolished and replaced by a series of gas stations (southwest corner of Vermont and Clinton). [If anyone out there has a photo of the building, please contact me.]

The GLF office became a beehive of gay political organizing that propelled the Gay Liberation movement in Southern California forward rapidly (more about all that activity in the future). In a recent event at USC-ONE Archives, Dr. Craig Loftin, Lecturer in gay history at California State University (Fullerton), described that year as follows, “…1970 was an incredible year of achievement for GLF in Los Angeles. They staged marches, protests, ‘zaps,’ interventions, and a broad range of other militant, highly visible actions. They fought back. They led the march out of the shadows, out of the closets.”

(Photo credit: Author’s collection)

On 9/18/1970, GLF staged a “Touch-In” in a popular WeHo bar, The Farm; at 10 p.m. gay men reached out and hugged each other; L.A. Sheriffs arrived and were warned by GLF: if you arrest one of us, you’ll have to arrest all of us; men continued to show affection for each other; chanting began: “Ho-Ho, Ho Chi Minh, GLF is going to win;” Sheriffs retreated; the beginning of the end of police raids of gay bars in L.A. was upon us.

While Kight and I played a leadership role in those developments, let me make this clear: a handful, then scores, then hundreds of gay and lesbian people—all voluntarily engaged activists—collectively and constructively made it happen, a record of accomplishment probably unmatched by any other GLF in the country.

In this essay, I will focus on one of those 1970 activities, the GLF Gay Survival Committee and the subsequent Hoover Street Commune because there is a clear path, through thick and thin, from that Committee to the Commune to the October 1971 opening of the Gay Community Services Center in Los Angeles (now called the L.A. LGBT Center), the first and, then as now, the largest in the world. GCSC also seeded what grew into a world class gay community in Los Angeles.

The Gay Survival Committee, the name tells you where gay people were at that time, was created in the Spring of 1970 when I proposed the idea to GLF which approved it unanimously. The Committee’s primary purpose was to begin exploring the possibility of offering—out of the GLF office and by referral—services specifically designed for gay and lesbian people suffering from oppression sickness (peer counseling, consciousness raising groups, Vietnam War draft and military resistance counseling, and medical and legal referrals). A Los Angeles Free Press article in August 1970 caught the zeitgeist of that GLF effort.

By the end of 1970, L.A. GLF was beset by a mostly friendly, fundamental debate as to which direction to go in 1971, either in an evolving liberation direction or a more social direction by opening a Gay Coffee House with entertainment. After much internal discussion and to resolve the tension, I made a proposal in December 1970 that the GLF office be closed and that GLF financial resources, totaling about $900, be turned over to the Gay Coffee House project. GLF members agreed.

Early in 1971, a Gay Coffee House was opened by GLF stalwarts John Platania, Jim Kepner, and others in a storefront on Melrose Ave., a site where the Continental Baths subsequently stood (western corner of Melrose and Kenmore). After several months it devolved into a crash pad, could not pay its rent, and closed.

During 1970, my thinking had also evolved considerably from the Gay Survival Committee’s idea of providing limited services out of the GLF office to contemplating a more substantial, comprehensive, freestanding operation providing direct services and infused with the radical spirit and methodology of Gay Liberation. Also, during that year, I grew by leaps and bounds, transforming from a somewhat quiet, introverted academic type into an articulate, assertive community organizer because of GLF’s one-after-the-other successes.

The more I read, dialogued with others, and self-reflected, it was gradually becoming clearer to me that if we were going to succeed as a liberation movement, it was critical that we enlarge our GLF agenda from merely a reactive strategy of fighting back against hetero supremacy into an enlarged, transforming proactive strategy of building a visible, organized, self-accepting, and defiant gay community where none had ever existed.

This new way of thinking began a first level of envisioning that a gay center might be the vehicle around which such a gay community could coalesce. I did not know exactly how GLF could make that happen. As it turned out, I became the vision carrier for such a project, although at that time I did not know that term nor understand what it meant. I just did what I did from a deep well of caring and intense gay liberation motivation. I did know, however, from my many learning experiences as I matured during my 20s, that the path forward reveals itself as we walk the path not as we think about it or discuss it. And it worked.

[I want to acknowledge the important work done by Rev. Troy Perry, whom I admire, in founding in 1968 in Los Angeles the Metropolitan Community Church

which became an important part of the gay community in L.A. and elsewhere. The roots of MCC were in evangelical Christianity and the Society for Individual Rights, a conservative homophile organization started in 1964 in San Francisco. The roots of the Gay Liberation movement, however, were in the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion.]

On January 1, 1971, a year after opening the GLF office on North Vermont Ave., a contingent from GLF consisting of Randy Schrader, Steve Beckwith, Stan Williams, Rod Gibson and me, members of GLF’s Gay Survival Committee, moved into the newly created Hoover Street Commune which became the relocated activist center for Gay Liberation militancy in L.A. Morris Kight and others became an essential part of the organizing activities taking place there.

Thus, began the second phase of the pioneering work of the L.A. Gay Liberation Front.

Hoover Street Commune (1971-1973): GLF Implements a Strategic Plan for a Gay Community Center

One of the important gay historical sites in Los Angeles is located at 1500 North Hoover Street (at Sunset Dr.), right behind the then KCET public television studios (now the Scientology Media Production Studios) on Sunset Blvd. in Silverlake. It was the home of the Hoover Street Commune, which existed from 1971 until 1973—the place from which the building of the gay community center and, by extension, a gay community in Los Angeles emerged.

[Community organizers today have many exquisite organizing tools that we did not have in the 1960s and 1970s; however, missing today is the communal living that focused and magnified our effectiveness. When I dialogue with young activists today, the absence of such an essential tool in their organizing efforts is glaring.]

The house, built as a duplex, had been turned into one large house with five bedrooms, two bathrooms, a small kitchen, a dining room, and a living room. The original communards included very creative Stan Williams, a former Sonja Henie and Ice Capades skater; Steve Beckwith, a suit-and-tie businessman; Randy Schrader, a recent UCLA Law School graduate studying for the California Bar exam; Rod Gibson, a young GLFer; and me. Occupancy was a bit fluid at first, but then stabilized. Gibson soon moved out and was replaced by Ray Powers, a Hollywood actors’ agent, and Beckwith and his lover, Van Brown, a student at UC Santa Barbara, needed more privacy and moved elsewhere, replaced by John Platania.

GLF members Llee Heflin, Dexter Price, and Bruce Cristoff lived right next door at 1502 N. Hoover St. In and out on a regular basis were Morris Kight, Tony DeRosa, June Herrle, Howard Fox, David Backstrom, John Coffland, Justin Dangerfield, John Murphy, my beloved Luke Johnson, and many more. The door was always open.

For me, living there was like being in an always-in-session Graduate School for Advanced Gay Studies, intellectually and spiritually stimulating like nothing I had known before. I was being introduced to gay-centered films, books, art and artists, poetry, ideas, music, personages, spiritual lineages, inventive gay Kama Sutra positions, and much more that were all new to me.

Williams had created a large, low dining table and we sat on the floor to eat; once a week each member prepared supper. Virtually every evening there would be eight to ten people sitting around our large communal table for supper—visiting gay liberationists, soon-to-be-famous filmmakers, writers, and poets, grifters, lovers du jour, the Marlboro Man, mystics, future judges—a gay Noah’s Ark—engaged in animated and liberating discussions.

Sometimes Lucy would come down from the sky with her diamonds to visit. Williams and Platania would put their long hippie hair up into elegant beehive hairdos to go shopping at the local Safeway grocery store, an aspect of Gay Liberation’s political fight against rigid hetero gender norms. GLF called it “Gender Fuck,” a militant precursor of “Gender Fluid.” Williams created a High Tea which was poured many afternoons at 4 p.m. with rolled joints on a silver platter. Spirited political discussions would go into the night. And so it went.

In this exhilarating and creative gay-centered vortex at the Commune, sight was never lost as to why I was there—transforming the work of GLFs Gay Survival Committee into a gay community center. At both the GLF office and the Commune, the Committee’s composition was fluid with people coming and going. However, a more or less stable core group formed over time consisting of Beckwith, Kight, Platania, Williams, Schrader, Herrle, and Howard Fox among others. My role as the Committee’s founding chairman was to provide the leadership and glue to hold things together and guarantee there was forward movement by calling and chairing meetings every two weeks, preparing agendas, facilitating discussion, and ensuring continuity and follow through between meetings.

A revolutionary opening of historic proportions was being created by GLF in L.A. and we collectively leapt through that opening with the most serious intentions and joyful exuberance. Among the critically important developments that grew out of the Hoover Street Commune during those years were the following:

- Development of Content Architecture of a Gay Community Center: Every two weeks, I called a working meeting of the Committee at the Commune where contours and content of the groundbreaking gay center were collectively discussed and agreed to.

After each meeting, Platania and I would meet for an extra hour writing down what we had heard and agreed to in the meeting. Platania had worked as a grant writer for the City of Los Angeles’ Community Development Department and TELACU (The East Los Angeles Community Union). I typed up our writings, and by May 1971, an impressive looking, forty-page, bound proposal emerged from the Committee’s collective work that delineated the reasons for such a gay center, described the comprehensive human services to be provided in a community-based context, and laid out a timetable for implementing each component.

That document became an invaluable organizing tool because it clearly described what we planned to do and how we planned to do it. The proposal clearly sent a powerful message that these gay liberationists were very serious about their intentions, with a blueprint and hammer and nails in their hands, and ready to go to work. The name: “Gay Community Services Center.” Words never seen before anywhere.

“Gay” because we were totally in your face about who we were, not hiding behind camouflage words as was done prior to Gay Liberation. “Community” because of the core values implied in that word: (1) a community is a unified body whose members assumes responsibility for each other, meaning everyone, and (2) a community was what we were trying to call into being. “Services” because we were planning to deliver services specifically designed to meet the needs of gay, lesbian, and trans people, mending the deep woundings caused by hetero supremacy and invoking the new possibilities of gay empowerment. “Center” because of our intention that it be a center around which a gay community would coalesce.

- Creation of a Non-Profit, Tax-Exempt Organization: This idea was particularly advocated for by me and resulted in several people leaving the Committee, feeling that GLF was changing into an establishment organization, which was a foolish thought given how outcast and vilified gay people were at the time. No establishment would touch us, even most so-called homosexuals at that time avoided us and were afraid that GLF’s radical ideology and fighting back through direct action would get us all in more trouble.

My position was that we were attempting to create a gay community center and a gay community, both ideas revolutionary developments for our people at that time. GLF was building something that would hopefully outlive all of us and a community called for solid community institutions serving the people.

Moreover, one of the successful tactics of the Gay Liberation movement was keeping the hetero supremacists off balance. They never could conceive of gay and lesbian people developing self-respect after the centuries of violent intimidation and instilling of fear. They never expected the audacity of gay liberationists in L.A. creating a community center and envisioning an actual gay community that was real, substantial, and angry, that fought back and thumbed its nose at their supremacist proclivities and actions.

Beginning in April 1971, attorney Allen Gross and I began the grunt work of incorporating the proposed community center in California. Gross, an important hetero ally and lifelong friend, had founded the Legal Aid program in Oregon and served as legal counsel for L.A. GLF. He would serve for 25 years as legal counsel to the Center. We prepared Articles of Incorporation and By-Laws to submit to the State of California and could not read how the documents would be dealt with by the newly elected California Secretary of State, a young fellow named Jerry Brown. The documents were returned approved in two weeks and Brown became a dependable ally of gay people in California.

The same could not be said for the federal IRS tax exemption process, which routinely should have taken a few months, but in our case took five years. Gross prepared the IRS application with great care and attention to all possible traps that could be used to deny us. Decades later, I was informed privately that the Nixon White House had instructed the Secretary of the Treasury to put our application in his desk drawer and not act on it.

In 1972, I was summoned to Washington, D.C., for a special interrogation by Frank Cerny, head of the exempt branch of IRS, in a bizarre scene that unfolded in a majestic hall that was truly a surreal experience. With Gross on one side of me and attorney Ed Dilkes of L.A. Legal Aid on the other side, and me resembling a hippie Hasidic rabbi, I recited calmly over and over again what Gross had skillfully written in our application—we would serve anyone who asked for our philanthropic services and we would turn no one away, which were the exclusivity grounds on which IRS planned to trap and deny us tax-exemption. In 1976, our relentless perseverance and political pressure finally forced the White House and IRS to approve our tax-exemption application. GCSC was the first openly gay organization to secure IRS non-profit, tax-exempt approval—a singular achievement then.

- Opening First Liberation House. By mid-1971, the search began in earnest to find a location to open the Center, but initially nothing suitable could be found. That did not stop us. In August, Platania found a house on North Edgemont Ave. in East Hollywood, just south of Sunset Blvd., where the newly formed Center opened a Liberation House, the first of many in its Liberation House program over the years. Ralph Schaefer, a core GLF member, became its resident manager.

(Photo credit: Author’s collection)

The Edgemont Liberation House provided free housing primarily to young gay men, often runaways who were homeless. From 9 a.m. until 4 p.m. residents were out of the house looking for employment, getting back into school, or whatever. When the residents returned to the house at 4 p.m., under Schaefer’s supervision, they collectively made supper for the house.

The key words for living in a Liberation House, as in organizing the Center

itself, were “mutuality” and “cooperation.” Evening activities at the Edgemont house included a group discussion led by Schaefer or another GLF member that amounted to a gay consciousness-raising group, something the residents had never experienced before—gay and lesbian people viewed in a positive, constructive light. The residents blossomed. After breakfast in the morning, residents headed out to lean into their goals for the day.

Opening of the L.A. Gay Community Services Center

In September 1971, Platania found a possible site for the Center in an old Queen Anne style home at 1614 Wilshire Blvd. at Union Ave., just east of MacArthur Park. Committee members looked at the house and all agreed—yes, let’s do it. I was the full-time+ founding executive director and Kight, Herrle, and Platania became members of the first Board of Directors.

After a bit of cosmetic fix-up, the installation of telephones, and a big sign in front emblazoned with the words “Gay Community Services Center,” the year and a half of relentless organizing work by GLF members led to fruition. The story of that Center and the gay community it facilitated in Los Angeles, including the role of the Highland Park Collective, will be told later, but this was how GLF got that far.

To give you an idea how revolutionary this community organizing was in the lives of gay people, after the sign was hung on Wilshire Blvd., a call was received at the Center from an important gay figure telling us, “You must take that sign down immediately! You people are going to get all of us arrested!” Then, most gay people rightfully lived in fear.

- The Gaywill Funky Shoppe: The story of the Hoover Street Commune would not be complete without mentioning the Gaywill Funky Shoppe, a thrift store the Center opened in 1972 in Silverlake.

Amazingly, all the organizing and sustaining of the Center was accomplished with little money or no money at all. The organizers were fueled by something much larger than money. What little funds the early Center did operate on came from three primary sources: (1) Friday night Gay Funky Dances in Hollywood, open to all ages, which were started in 1970 by GLF, went on hiatus when the GLF office closed, and were started up again in August 1971 sponsored by the Center. After expenses, the dances generated about $150 a week; (2) donations at the Center raised about $150 weekly; and (3) after expenses, the Gaywill Funky Shoppe brought in about $200 weekly.

(Photo credit: Author’s collection)

Central to the Shoppe was Commune member Stan Williams assisted by young GLF members Dexter Price and Bruce Cristoff. Using a gift possessed by many gay men of being able to transform ordinary junk into objets d’art, the thrift shoppe thrived. It was located at 1531 Griffith Park Blvd., where that street meets Sunset Blvd. in Silverlake, occupied today by the Pine and Crane Restaurant. When Williams left for San Francisco, Ralph Schaefer took over as manager.

One day early in 1973, after not hearing from Schaefer for several days and hearing that the Shoppe seemed closed, Kight and I went to check it out. We found Schaefer dead in the bathroom with a bullet hole in the back of his head. He had been executed. Robbery was not a motive since a visible cash box was untouched. The murder of gay men occurred often then with assailants rarely looked for or apprehended by the LAPD. One less fag was a blessing for hetero supremacists.

The LAPD Rampart Division called Kight and me in for questioning and tried to pin the murder on us, demanding that we take polygraph tests.

We gave the LAPD the middle finger, telling the investigators to arrest us if they wanted to, but we refused to play their disrespectful game regarding someone we valued so dearly, and walked out. The LAPD was not heard from again regarding Schaefer’s murder, even after numerous requests for information.

The Gaywill Funky Shoppe was permanently closed immediately as a show of respect for Schaefer.

At the beginning of this article, you were advised to remember that all this GLF organizing was being done under the most difficult community organizing conditions imaginable. Even under those horrendous conditions, however, you can clearly see that something historically significant had occurred in Los Angeles that took place nowhere else in the same way in the lives of gay and lesbian people, facilitated by a vanguard of young gay liberationists.

By October 1971, with the opening of the Gay Community Services Center, with much more revolutionary struggle ahead, a whole new realm of possibilities and ways forward began opening up for gay and lesbian people in Los Angeles. The GLF Gay Survival Committee and Hoover Street Commune had done their early community organizing work impeccably.

A unique revolution in consciousness and liberation unfolded in Los Angeles, radically changing the quality of gay people’s lives and welfare, instilling a new, life enhancing identity and birthing an exciting, emerging community where we learned to value and take care of each other. The ripples of that Gay Liberation revolution wash over us still today.

******************************************************************************************

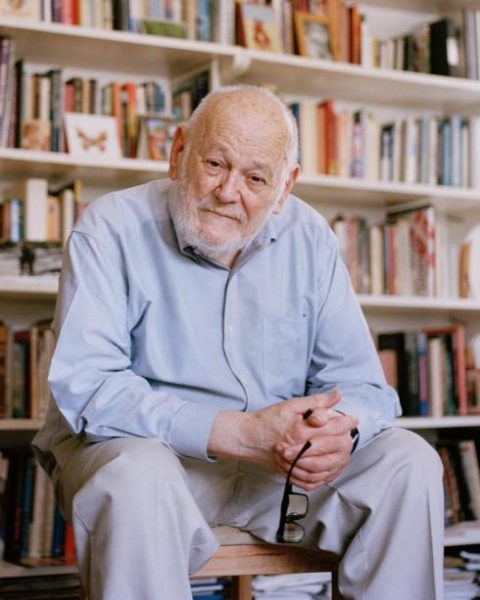

Photo by Todd Danforth

Don Kilhefner, Ph.D., played a pioneering role in the creation of the Gay Liberation movement and is co-founder of the L.A. LGBT Center, Van Ness Recovery House, Radical Faeries, and has been a gay community organizer for 55 years in Los Angeles and nationally. [email protected]

Features

New mayor Chelsea Byers, hopes to make WeHo a model city for others to follow

She has big plans, but can they withstand the Trump administration?

West Hollywood’s new mayor Chelsea Byers has lofty ambitions to make the 1.8-square-mile city, a model for other cities in the region.

She hopes to deal with compounding crises of housing affordability, traffic congestion, climate change and a new federal government that’s slashing programs and services many people – especially LGBTQ people – rely on.

But can Byers, who was elected to city council in November 2022 and selected as

mayor by council in January, really make a difference during her one-year stint in the

city’s top job?

Byers believe she can.

On one of the biggest challenges facing West Hollywood residents – housing

affordability – Byers fully embraces more housing development.

“For 80% of the city of West Hollywood including myself, who are renters, accessing a

home that is affordable is a very difficult thing. And the way that cities can address that

cost is frankly, by building more housing,” said Byers.

Byers also says she fully accepts the state’s regional housing needs assessment, which

assigned West Hollywood a target of building 3,933 new housing units in the next eight

years. That’s a tall order, given the city is currently only home to about 38,000 people.

“We’re going to have to look at this sort of invisible cap that we put across the town to

increase the capacity in a way that is equitable, that creates more opportunity for

different types of housing to be built. We wouldn’t want all of this rezoning to help us

lead to more one-bedroom apartments, when we know that the future of the city is also

accommodating more families,” said Byers, noting that queer families also struggle to find

homes in West Hollywood.

Those housing targets also dovetail with the city’s long-standing ambition to have

Metro’s K-Line extended through West Hollywood, Byers says.

But even if West Hollywood meets its targets, it’ll only be a small drop in region that

studies estimate needs to build more than 600,000 units of affordable housing. Still,

Byers says West Hollywood can lead by example and get buy-in from the other cities in

LA County to help solve the affordability crisis together.

“I believe that our values can be extended to these other places and help move them

actually in big ways,” said Byers.

Those values necessarily include West Hollywood’s historic diversity and inclusivity of

its LGBTQ+ and immigrant communities, both of which are feeling ill at ease from the

federal government’s attacks.

“I think it goes above and beyond the fear-mongering and outright assaults that the

current federal administration’s lobbying at the LGBTQ community. It’s the real

dismantling of funding and structures that existed at the federal level to enable a lot of

the social service programming that our LGBTQ community members rely on,” said Byers. “That is the biggest thing that we feel right now when I’m asked as a city leader,

how are we impacted?”

The city is responding to this looming threat through its own funding process.

“We’re at the start of a three-year cycle that determines how, which organizations, we

invest our $7.8 million social service budget. To have these two moments happening at

the same time gives the city a tremendous opportunity to step up to whatever extent we

can,” she said, noting that programs for sexual health care, HIV programs, and aging

in place are particular priorities.

“Part of what I’m doing is creating funding that is accessible and available in more rapid

ways than our three-year cycle. Because once the three-year cycle has closed its door,

then that is it. One of those tools is a micro grant program that is specifically dedicated

towards Innovative or programming that that is needed,” Byers said.

Part of the response is also ensuring that West Hollywood remains a beacon for LGBTQ

people not just in Los Angeles, but across the country and around the world.

“You’ll see us as the city not back down from our investment in programs like Pride

which are world-class events,” she said. “For us, this is the thing that matters. And

we’re willing to make the additional investments in the public safety resources to make

sure that it’s going to be a safe event.

“I think a lot of our community members have always felt like they are a target already,

and it hasn’t stopped anyone from doing their thing. In fact, if all eyes are watching, then

we better give them a good show, has been our attitude.”

Earlier this month, city council voted to officially designate the Santa Monica strip

between La Cienega and Doheny as the Rainbow District, with a dedicated budget to

improve and promote the area as a destination. The area will soon see new street pole, banners, utility wraps, murals, and the West Hollywood Trolley bus will have service

extended to Thursday nights to help promote business along the strip.

Byers says the city is also looking at reducing red tape around how business spaces are

licensed to help revitalize the area.

“We’ve often said that West Hollywood is a model for how it gets done,” said Byers. “It’s

such a beautiful moment for us to sort of pivot our focus locally and remind ourselves

that cities are about quality of life, and making sure that we can be an inclusive city.”

Features

Los Angeles Blade kicks off Free Community Event Series with an informative political panel of government and advocacy group leaders

Time To Get Informed, Time To Resist will be hosted by The Abbey on Saturday, April 19th at 10 am, as an open forum to present the current political climate as it affects SoCal for the queer community and beyond.

Time To Get Informed, Time To Resist will be hosted by The Abbey on Saturday, April 19th at 10 a.m., as an open forum to present the current political climate as it affects SoCal for the LGBTQ community and beyond.

In its commitment to be a thriving resource for the SoCal community, the Los Angeles Blade, in partnership with Roar Resistance, will present its first free community event. The Time To Get Informed, Time To Resist panel will include government and advocacy group leaders who will discuss political news regarding the LGBTQ community and beyond, as it affects residents and business owners in California. The panel will also share different ways the community can activate and get involved. The event will conclude with a Q&A session.

The panel will be moderated by non-profit activist Michael Ferrera, representing Roar and will include Mayor of West Hollywood, Chelsea Byers; Jorge Reyes Salinas, Communications Director of Equality California; Abbe Land, former Mayor of West Hollywood and Co-Chair of Roar, Chris Baldwin; NAACP LGBTQ+ Committee Chair and Nico Brancolini, Political Vice President for Stonewall Democratic Club.

“We need to focus on the real issues to effectively resist. This forum will serve to educate concerned citizens and help them act locally to achieve this goal,” said Ferrera.

Join us for this free event on Saturday, April 19th at 10 am at The Abbey.

For more information, contact [email protected]

Features

Finding love in queer Los Angeles with matchmaker Daniel Cooley

Is it hard to date in queer Los Angeles? We do a deep dive into finding love with one of the community’s most in-demand matchmaker.

For those of us gay singles in Los Angeles, we know that dating can be difficult. In addition to all the usual dating issues, the queer community also has to deal with body issues, open relationships and hookup apps. Even with a large population of queer folk, trying to find love in Los Angeles can often seem futile. Is it possible to find love in today’s tech age?

Enter professional matchmaker Daniel Cooley, co-owner of Best Man Matchmaking, on a mission to help LGBTQ+ folks find real love and long-term commitment. You may have seen him see him pop up on TV, or may have heard about his packed singles mixers.

He and his full team (which even includes an astrologer and stylist) have a system that is tried and true. He is fully in tune with the challenges that queer singles face. We sat and chatted about it all—dating apps, monogamy, red flags, first dates, and more!

How did you get into the world of matchmaking?

A decade ago I appeared on the reality show “Millionaire Matchmaker” as a match for underwear designer Andrew Christian. I remember looking up to Patti Stanger’s ability to help singles understand the reasons why they might be single—she was so fierce and fabulous. Around that same time, I had also started a nonprofit focused on HIV-related needs. Within that non-profit, I helped build a large social network and club—made up mostly of gay, bi, or queer men. People would constantly ask me if I knew anyone in the group who was single.

I became known as the “divine connector,” always linking people to opportunities—whether it was a job, a new friend, or a date. I curated tons of long-term relationships, marriages, and lasting friendships. Years later, when I began to sell real estate, my single clients would often ask if I knew anyone they could potentially share their new home with.

That’s when I reached out to the only gay matchmaker I knew at the time, Mason Glenn, who used to run The Gay Matchmaking Club in Los Angeles. He introduced me to Anthony Canapi, who was working for a local matchmaker and eventually founded “Best Man Matchmaking”—working with him as a recruiter and matchmaker. Now I am the co-owner and CEO of “Best

Man Matchmaking.”

In your opinion, what are the biggest challenges today in dating in the LA

queer community?

One of the biggest challenges with dating in the queer community is that many people haven’t done the inner work. Instead of connecting over shared morals, values, interests, and genuine connection, a lot of guys—especially those struggling with low self-esteem—are constantly chasing the next best or hottest thing.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve tried to help men be more realistic with their expectations, but the response is often, “Well, he hooked up with me on Grindr, so why wouldn’t he date me?” The truth is, just because someone hooks up with you doesn’t mean they want to build a relationship with you. Swipe culture, hookup apps and social media have made dating more difficult—not just in the queer community, but across the board. Add to that

the trauma and insecurities many gay men are still working through, and it becomes even harder. Rejection from society is one thing, but rejection from within our own LGBTQ community—whether in dating or just trying to make friends—can be deeply painful. I hear horror stories all the time from gay men who feel consistently shut out by the very people they’re trying to connect with.

At what point should people turn to matchmaking to find a possible match?

There’s really no right or wrong time to turn to a matchmaker—but we recommend you begin the process before you think you’re ready. Some men wait until they are completely frustrated and exhausted dating on their own and that’s usually too late. You want fresh eyes and an open heart getting the process started with your matchmaker, not a jaded outlook.

Most of the clients we represent hire us because they value privacy and have a clear idea

of who they seem themselves with, coupled with the ongoing inner work of understanding what they have to offer their partner. And I’m not talking about physically or financially – the clients we place in relationships the fastest are the ones who know themselves really well. Did you know that recent studies show people are spending an average of 27 to 45 hours a month on dating apps? That seems unhealthy to me.

I love when my clients tell me that working with us feels like meeting someone “the organic way.” Like they are being introduced to a great match through a trusted friend. Hiring a matchmaker is like having a close friend who knows you really well and has access to a network of high-quality, relationship minded men. It’s that simple.

What are the biggest factors that you consider in matching people up?

Our matchmaking is based on 4 core concepts:

Morals & Values:

We look at core beliefs—how someone lives their life, what they stand for, and how they treat others. Shared values create long-term compatibility.

Interests & Lifestyle:

Do they enjoy the same things? Travel style, social life, routines—these everyday details matter when building a life together.

Sexual Compatibility:

This is especially important for gay men. Desire, preferences, and position in the bedroom. You can’t leave this out because it can make or break a connection.

Relationship Intentions:

We match people based on where they are emotionally and what kind of

relationship they’re ready for—not just who they’re attracted to.

What are some red flags that someone should never ignore?

There are two main red flags we screen for in matching our clients. Unclear communication is a major red flag. It’s one thing to be busy, but if they’re taking days to reply or you’re always the one initiating plans, that shows a lack of effort. Don’t expect that to magically change—poor communication doesn’t improve unless the person is actively working on it.

If someone says they are not sure what they want out of a relationship or connection, this is another red flag for us. For example, if they say they’re open to a relationship “if it happens,” but aren’t clear about wanting something long-term—believe them. Take their words seriously and move on. It’s better to invest your time in someone who knows what they’re looking for.

In your opinion, what would be a good first date?

A great first date involves doing something you genuinely enjoy—whether it’s trying out a new restaurant, hiking a trail you’ve been meaning to explore, or visiting a museum you’ve had your eye on. If your date enjoys it with you, there’s a good chance you’ll naturally connect. We’ll curate a first date for our clients that reflects their lifestyle, hobbies, and life stage.

What are the biggest mistakes people make when going on a date?

There’s one that we look out for.

The biggest mistake is not staying present. People often talk too much about themselves out of nervousness, instead of asking questions and getting to know their date. A common slip-up is bringing up an ex or sharing recent drama in their life. Leave the drama at the door and focus on enjoying the person in front of you.

It seems that monogamy has become less popular in relationships. Is this

true?

Monogamy is still very popular. Over 80% of the people who reach out to us are looking for a monogamous relationship. The rest may be open to something more flexible, like “monoga-mish”—meaning they’re in a committed relationship but open to exploring non-monogamy down the line—or they’re simply open-minded about different dynamics.

Our clients are men who are looking for the same kind of companionship many people want: a long-lasting relationship, emotional connection, and a true partner to build a life with.

Can open relationships work?

Absolutely! The one thing that’s absolutely necessary for any relationship to work— trust. The only way to build trust is to communicate your needs clearly.

If you’re in an open relationship and you’re sneaking around sleeping with everyone without being honest with your partner, chances are it’ll never work out. But if you’re transparent, if you let your partner know you love them and your needs also include connection with others—and they’re comfortable with that—then there’s no reason it can’t work.

We know the world of apps has changed the dating scene. Is it possible to

meet a quality date from an app?

Definitely.. But unfortunately, it’s more a matter of luck and timing to meet someone who’s actually relationship-ready, emotionally stable, financially secure, and checks most of your boxes.

You can meet your match anywhere! We encourage our clients not to put all their eggs in one basket. Many leave the apps on their own because they’re tired of wasting time with people who aren’t as serious about dating as they are. But others see the value in putting themselves out there in lots of different ways and love having our support while swiping.

What’s the best piece of advice you can give single people who are looking

for a relationship in Los Angeles?

People are craving touch, connection, and love. Try approaching more people you find attractive in real life—whether it’s at the store, the gym, or a social event. Be bold and courageous—people find that attractive. It’s easy to get rejected online, but most people are tired of the apps and are ready for something more real.

This might be an unpopular opinion, but I’ve found that people in LA can be flaky and passive-aggressive.

I say: be direct. Let people know what you want. If it’s not a match, just be honest and let them know. Don’t lead them on, or ghost them.

What do you love most about matchmaking?

Matchmaking is both the most rewarding job I’ve ever had and the most challenging. My favorite part of being a matchmaker is when a client is genuinely excited and hopeful about someone they just met through us. It happens everyday. There’s nothing more rewarding than supporting someone get closer to finding the person they want to spend their life with. It’s priceless and makes all the hard work worth it.

What have been the biggest things you’ve learned in matchmaking?

Being selective about emotional compatibility and shared values is healthy and critical if you’re serious about meeting someone—but being overly picky about things like looks or having the “perfect body” doesn’t serve anyone long-term.

What is your message to the single queer community of Los Angeles?

Do the inner work. Ask yourself if you’re truly being the person you want to date. If not, what unhealed emotions or past experiences are holding you back? The moment you begin that work, you open yourself up to deeper, more meaningful connections.

Stay tuned for Daniel’s new love and dating Los Angeles Blade column, coming soon!

For more information, check out BestManMatchmaking.com

Features

Tristan Schukraft speaks on keeping queer spaces thriving

The new owner of the Abbey continues to expand to protect queer spaces

Like the chatter about Willy Wonka and his Chocolate Factory, the WeHo community started to whisper about the man who was going to be taking over the world-famous Abbey, a landmark and part of history in Los Angeles’ queer nightlife. Rumors were put to rest when it was announced that entrepreneur Tristan Schukraft would be taking over the legacy created by Abbey founder David Cooley. All eyes are on him.

For those of us who were there for the re-opening of The Abbey, when the torch was officially passed, all qualms about the new regime went away as it was clear the club was in good hands and that the spirit behind the Abbey would forge on. Cher, Ricky Martin, Bianca del Rio, Jean Smart, and many other celebrities rubbed shoulders with veteran patrons, and the evening was magical and a throwback to the nightclub atmosphere pre-COVID.

The much-talked-about purchase of the Abbey was just the beginning for Schukraft. It was also announced that this business impresario was set to purchase the commercial district of Fire Island, as well as projects launching in Mexico and Puerto Rico. What was he up to? Tristan sat down with us to chat about it all.

“We’re at a time right now when the last generation of LGBT entrepreneurs and founders are all in their sixties and they’re retiring. And if somebody doesn’t come in and buy these places, we’re going to lose our queer spaces.”

Tristan wasn’t looking for more projects, but he recounts what happened in Puerto Rico. The Atlantic Beach Hotel was the gay destination spot and the place to party on Sundays, facing the gay beach. A new owner came in and made it a straight hotel, effectively taking away a place of fellowship and history for the queer community. Thankfully, the property is gay again, now branded as the Tryst and part of Schukraft’s portfolio with locations in Puerto Vallarta and Fire Island.

“If that happens with the Abbey and West Hollywood, it’s like Bloomingdale’s in a mall. It’s kind of like a domino effect. So that’s really what it is all about for me at this point. It has become a passion project, and I think now more than ever, it’s really important.”

Tristan is fortifying spaces for the queer community at a time when the current administration is trying to silence the LGBTQ+ community. The timing is not lost on him.

“I thought my mission was important before, and in the last couple of months, it’s become even more important. I don’t know why there’s this effort to erase us from public life, but we’ve always been here. We’re going to continue to be here, and it brings even more energy and motivation for me to make sure the spaces that I have now and even additional venues are protected going in the future.”

The gay community is not always welcoming to fresh faces and new ideas. Schukraft’s takeover of the Abbey and Fire Island has not come without criticism. Who is this man, and how dare he create a monopoly? As Schukraft knows, there will always be mean girls ready to talk. In his eyes, if someone can come in and preserve and advance spaces for the queer community, why would we oppose that?

“I think the community should be really appreciative. We, as a community, now, more than ever, should stand together in solidarity and not pick each other apart.”

As far as the Abbey is concerned, Schukraft is excited about the changes to come. Being a perfectionist, he wants everything to be aligned, clean, and streamlined. There will be changes made to the DJ and dance booth, making way for a long list of celebrity pop-ups and performances. But his promise to the community is that it will continue to be the place to be, a place for the community to come together, for at least another 33 years.

“We’re going to build on the Abbey’s rich heritage as not only a place to go at night and party but a place to go in the afternoon and have lunch. That’s what David Cooley did that no others did before, is he brought the gay bar outside, and I love that.”

Even with talk of a possible decline in West Hollywood’s nightlife, Schukraft maintains that though the industry may have its challenges, especially since COVID, the Abbey and nightlife will continue to thrive and grow.

“I’m really encouraged by all the new ownership in [nightlife] because we need another generation to continue on. I’d be more concerned if everybody was still in their sixties and not letting go.”

In his opinion, apps like Grindr have not killed nightlife.

“Sometimes you like to order out, and sometimes you like to go out, and sometimes you like to order in, right? There’s nothing that really replaces that real human interaction, and more importantly, as we know, a lot of times our family is our friends, they’re our adopted family.

Sometimes you meet them online, but you really meet them going out to bars and meeting like-minded people. At the Abbey, every now and then, there’s that person who’s kind of building up that courage to go inside and has no wingman, doesn’t have any gay friends. So it’s really important that these spaces are fun, to eat, drink, and party. But they’re really important for the next generation to find their true identity and their new family.”

There has also been criticism that West Hollywood has become elitist and not accessible to everyone in the community. Schukraft believes otherwise. West Hollywood is a varied part of queer nightlife as a whole.

“West Hollywood used to be the only gay neighborhood, and now you’ve got Silver Lake and you’ve got parts of Downtown, which is really good because L.A., is a huge place. It’s nice to have different neighborhoods, and each offers its own flavor and personality.”

Staunch in his belief in his many projects, he is not afraid to talk about hot topics in the community, especially as they pertain to the Abbey. As anyone who goes to the Abbey on a busy night can attest to, the crowd is very diverse and inclusive. Some in the community have started to complain that gay bars are no longer for the gay community, but are succumbing to our straight visitors.

Schukraft explains:

“We’re a victim of our own success. I think it’s great that we don’t need to hide in the dark shadows or in a hole-in-the-wall gay bar. I’m happy about the acceptance. I started Tryst Hotels, which is the first gay hotel. We’re not hetero-friendly, we’re not gay-friendly. We’re a gay hotel and everyone is welcome. I think as long as we don’t change our behavior or the environment in general at the Abbey, and if you want to party with us, the more than merrier.”

Schukraft’s message to the community?

“These are kind of dangerous times, right? The rights that we fought for are being taken away and are being challenged. We’re trying to be erased from public life. There could be mean girls, but we, as a community, need to stick together and unite, and make sure those protections and our identity aren’t erased. And even though you’re having a drink at a gay bar, and it seems insignificant, you’re supporting gay businesses and places for the next generation.”

Features

Drag Race’s Honey Davenport New Fashion Line Is Making A Statement

Introducing Honey’s Hose: The World’s FIRST Drag and Black Queer Owned Inclusive Hosiery Brand by RuPaul’s Drag Race Legend Honey Davenport

Powerhouse drag performer, musician, DJ, activist and Drag Race alum Honey Davenport can now add entrepreneur to her long list of titles. A proud member of the leather community and fierce advocate for the LGBTQ+ and BIPOC communities is combining art, sensuality and fashion with her debut business — Honey’s Hose.

Developed alongside her best friend Saul Williamson, Honey’s Hose offers a wide variety of high-quality hosiery specifically designed for all skin tones, body sizes and budgets. Their mission is to empower individuals through style, comfort and confidence, celebrating self-expression.

Honey’s Hose will also establish the Honey’s Heaux Artist Fund to help emerging drag artists, enabling them to access the perfect hosiery for their performances.

After spending time crowdfunding, attending business seminars and accelerator programs, the line officially launched this weekend with a huge drag queen bash in Palm Springs. We caught up with Honey in between celebrating to talk about her new venture, the power of sexuality, supporting the Black and drag communities and what the future has in store.

Why has it taken so long to get drag queens and diverse body sizes represented in the hosiery industry?

Honestly, it’s baffling. For decades, the hosiery industry has clung to a very narrow, outdated ideal of beauty. It’s a reflection of a larger societal problem – the constant marginalization of anyone who doesn’t fit the ‘norm.’ Drag queens, with their vibrant artistry and fearless self-expression, have always been at the forefront of challenging those norms. Bodies of all shapes and sizes deserve to be celebrated, not ignored. It’s about time the hosiery industry caught up with reality and recognized the beauty and power in our diversity. It’s not just about selling hose, it’s also about acknowledging and celebrating who we are.

Every day there seems to be more and more attacks on the queer and drag community. As a queer, Black business owner, how do you think we are going to get through these next few political years?

It’s terrifying. It’s exhausting. But, as a queer, Black business owner, I refuse to be silenced. Our strength lies in our community. We have to support each other, amplify each other’s voices and never stop fighting for our rights. We’ve faced adversity before and we’ll face it again. Resilience, creativity and unwavering love for who we are – that’s how we’ll get through this.

We have to continue to create visibility, celebrate our joy and show the world that we will not be erased. We will continue to build our chosen families and create safe spaces for our community.

How can we best support the drag community?

Show up!

Go to the shows, tip the queens and celebrate their artistry. Beyond that, support businesses that are vocal allies. Speak out against hate and discrimination. Educate yourself and others about the history and importance of drag. Most importantly, listen to the drag community. They know what they need and they deserve our respect and support.

How can the queer community best support the Black community?

Listen. Learn. Amplify. Educate yourself about the unique challenges faced by Black queer individuals. Support Black-owned businesses, including Black queer businesses. Show up for Black, queer events and other movements fighting for racial justice. Call out racism within the queer community. Remember that solidarity isn’t just a word, it’s a commitment to action.

What have been some of the biggest challenges in creating Honey’s Hose?

Where do I start? Sourcing inclusive sizing has been a huge hurdle. Manufacturers just weren’t equipped to handle the range we needed. Finding the right colors to truly represent diverse skin tones has been another challenge. And of course, navigating the business world as a queer, Black entrepreneur has its own set of obstacles. But every challenge has been worth it. Seeing the joy on someone’s face when they finally find hose that fit and celebrate their skin tone – that’s what keeps me going.

Do you come from a fashion design background, what was the creative process in putting the line together?

My background is actually in musical theatre and I have mostly just excelled at being fabulous, though I’ve always had a passion for self-expression through fashion. Creating Honey’s Hose, was a process of listening to the community, identifying their needs and then working with talented mentors, collaborators and manufacturers to bring my vision to life. It was a life-changing effort, fueled by passion and a deep desire to create something truly special.

Besides representing all body types, what sets Honey’s Hose apart from other hosiery lines?

It’s more than just hose — it’s a statement. It’s about celebrating individuality, embracing our bodies and expressing ourselves without limits. We’re committed to quality, comfort and inclusivity in every aspect of our business. And we’re not just selling a product — we’re building a community. Honey’s Hose is about feeling confident, powerful and seen.

What do you love most about being a business owner?

The ability to create something meaningful. To build a brand that celebrates diversity and empowers people to feel good about themselves and create opportunities for others in my community.

What did you have to learn quickly about owning your own fashion line?

Everything! [But] never at the pace I expected. Seriously, it’s a crash course in business, design, manufacturing, marketing… I’ve learned to be resourceful and resilient and to ask for help when I need it. I’ve learned that passion and perseverance are essential ingredients for success.

Along with body diversity, you use your platform to promote sexuality. Why is it so important for queer people to continue talking about sex?

Because our sexuality is a part of who we are. It’s not something to be ashamed of or hidden away. By talking openly and honestly about sex, we destigmatize it, we empower ourselves, and we create a space for healthy conversations about pleasure, consent, and identity. Especially now, with so many attacks on our rights, it’s crucial that we continue to celebrate our bodies and our desires.

What are some basic hosiery pieces every queen should have in her closet?

A good pair of fishnets, of course! They’re a classic for a reason (and I do personally hope to one day create the best pair). Some bold, colorful tights to add a pop to any outfit and some comfortable, durable support hose for those long nights on stage.

Are we going to see more fashion designs from you in the near future?

Absolutely! Honey’s Hose is just the beginning. I have so many ideas and visions for the future. Stay tuned!

a&e features

David Archuleta celebrates his freedom

The American Idol alum channels George Michael with his latest single

Even the rain couldn’t keep the crowds away as American Idol alum David Archuleta took the stage at The Abbey in West Hollywood, celebrating the release of his latest single “Freedom,” – an homage to George Michael’s iconic anthem. “Freedom” comes on the heels of the 35th anniversary of the original anthem and it couldn’t be more timely as the LGBTQ+ community continues to face political persecution. The song celebrates Archuleta’s newfound freedom after coming out and dealing with a complicated relationship with his Mormon upbringing, while exploring his sexuality.

Archuleta happens to have been born the year Michael released “Freedom.” His music served as an inspiration in Archuleta’s coming out. Michael’s music took on new meaning for Archuleta, celebrating a freedom that he craved for himself growing up. Being able to pay homage to Michael is a testament to the personal growth Archuleta experienced since coming out in an Instagram post in 2021.

“I’m finally free from worrying about what is right. Does that look okay? Am I within the lines I’m supposed to? None of that really matters. Of course, we want to still be good, but the things I thought I needed to do, or the way I had to behave or act or say or think to be good, I now realize was a construct that someone else had. They were very black and white and the community that I was in created this safe little space that worked to an extent for certain people,” said Archuleta in an interview with LA Blade.

“Now I realize that they didn’t have all the answers that they told me and convinced me that they had. Sexuality, especially when it comes to queerness, is not what they thought it was. I can go ahead and live my own life now and it’s okay to explore that sexuality and sensuality. I’m an adult. It’s the freedom to explore yourself and also create a new identity in yourself after trying to live someone else’s idea of what you’re supposed to be your whole life up until your thirties.”

Archuleta’s vocals are soulful and mature here. He pays homage to the original, but also makes it his own.

“I thought it was a great message to tap into. It is an iconic song with an iconic video and quite the story that he had. He was a pop star, a heartthrob, and didn’t choose to come out. He got outed and he just owned it. There could have been a lot of other ways to go about that and I feel like the way he did it was so powerful and made him even more legendary because he really tapped into his sensuality and continued to consistently be one of the greatest pop stars in the world,” said Archuleta.

“I tried to stay pretty true to his version. At first, we actually made a dance version of it but decided to backtrack from it and say, you know what? This is George’s legacy and it’d probably just be better to just stay true to his energy that he put into it. And also stay more true to my energy. I decided to stay true to an MTV unplugged version that he did with a choir. I have gospel roots. I still love gospel music even though I don’t believe in it and what it’s saying and the messaging like I did before,” he reflected.

“It used to be everything for me, the performance in the emotion and the way you connect in your core to singing. I thought it was a beautiful way to combine my two passions of moving forward and being free, but also loving the soul in music. I felt like there was some great soul energy in there. I was able to get really gritty, even get a lot of growling, something I haven’t done for quite a while, I feel like in my music,” he said.

“Freedom” comes at a time when every day LGBTQ rights are being called into question. The timing is not lost on Archuleta.

“I think it’s unfortunate that the LGBTQ+ community always has to be targeted because of being a smaller group. Living our lives does not really enter fear with anyone else. But because fear-mongering works in the news, it works in politics, it works in rallying people behind someone to feel like they have to fight this cause. They are blaming the community for issues and fear-mongering and feeling like the queer community’s a threat to families and to religion. When a lot in the queer community are religious. They are actively participating and fully believing and are a part of families. They have children of their own. It’s just strange that politics click baits and instills fear to not take responsibility for the real issues that are actually impacting people. We were making great progress. It was so much easier for me to come out when I did versus when George Michael came out and now it’s back to a place where the fearmongering is getting people, especially the trans community.”

Archuleta’s personal journey continues to evolve. He has certainly thrown off the shackles of being branded as the innocent Mormon kind on American Idol.

“I don’t really know what my brand is anymore. I think as I release “Freedom,” it’s kind of like a rebranding. I’m still me, but I’m still also evolving. I feel like I’ve changed so much in the last two years. I’m having a fun time. I keep trying to push my boundaries and say yes to things that I wouldn’t have before. Even to the point where I’m writing songs and writers will be like, “David Archuleta can’t say that!” I’m like, well, I just did and I’m David Archuleta. But people sometimes feel weird and I guess it’s because I’ve always been squeaky clean. I’m not a Mormon anymore. I’m out and I don’t really have this religious ideology that I have to abide by. I am David, but I don’t have the same limits on me that I had before.”

Archuleta has more new music on the way and this summer, he will release his memoir. Writing his book was bittersweet for David, revisiting his past came with a few bumps along the way.

“I feel like it was traumatic. I had to take breaks. It’s like opening Pandora’s box going into your childhood because I feel like sometimes I’m too honest. You see some of the faulty programming that you still have wired in you and you kind of question like, why am I still abiding by that? If it happened so long ago, why am I still letting it affect me? Why is it still part of my belief? I’ve had to work through a lot and it’s been a more difficult process than I thought it would,” he said.

“I thought it’d be hard to write because I didn’t know what I was going to talk about. But that wasn’t the hard part. What’s hard is processing the emotions, the anger, the grief, the anxiety, the traumatic responses you have. But it’s been good. I’ve definitely processed a lot of my religious things. I’ve processed a lot of my internalized homophobia and just sexuality in general. It’s been interesting to reflect on the root of all of those things. And not just ideologies, but just realizing it’s not just a belief, it’s sometimes your genetics that make you the person you are. A lot of good self-reflection for sure,” he continued.

Archuleta’s fanbase continues to thrive along with each evolution the singer has gone through. He is grateful for his fans and his mission to remain true to himself is also for his fans. There is sincerity and truth at the heart of his music.

“To my fans, thank you for being here still and for enjoying what I’m doing, for cheering me on as I grow, as I fumble. I didn’t think fumbling and making mistakes was okay to do. I thought that for some reason if you make mistakes, you’re supposed to be unforgivable. And to see how forgiving of a following I have to let me learn and to experiment and to explore. That’s why I relate to George Michael’s “Freedom” because he had to explore in front of people. And of course, you want to keep parts of your life private, that’s what I prefer. But sometimes things just end up being people’s knowledge that you don’t even know, like processing religion and coming out, sexuality and dating and getting to know people and even learning how to be physical with someone,” he said.

“I’m going to continue trying to figure myself out. But for people to be excited and for me to finally have this part of time of my life is great. I just hope we continue having fun, unleashing more, and freely being ourselves and giving us the grace to figure that out even if it takes some time,” he concluded.

“Freedom” is now streaming on all major music platforms.

California

Community leader reflects on loss from the Eaton Canyon fire one month later

‘Showing up for community is actually very political’

Melissa Lopez, 46, was at home with ‘the coven’ – her two dogs Foxy and HoneyBee, and her two cats Stevie Nicks and Dulce – when she got a notification from Southern California Edison saying there might be a possible power shut-off in her area on the morning of Jan. 7.

Lopez lived right off of Lake Ave., in Altadena – a city that sits at the bottom of the Eaton Saddle near Mount Markham and San Gabriel Peak in the San Gabriel Mountains, part of the Angeles National Forest.

The fire stretched across 14,000 acres over the weeks it took to contain it. The latest report released on Jan. 27 by the LA County Fire Dept., listed 17 civilian fatalities, nine firefighter injuries and thousands of threatened, damaged and destroyed structures as casualties of this fire.

Lopez’s was one of the structures that was destroyed shortly after Lopez and her four pets evacuated.

She recalls that she was watching the news about the Pacific Palisades fire when the reporter got notice that there was a fire starting up in Eaton Canyon, announcing it live on the news. At that moment Lopez felt her stomach drop.

“The second I heard that, my stomach just dropped, because when you live in Altadena, you kind of get notices of brush fires all the time. But, I knew this time was different because of the intensity of the wind,” recalls Lopez.

Lopez, whose pronouns are she/they, is a licensed clinical social worker and mental health therapist who works primarily with queer clients in the Los Angeles area. They also have over 100 thousand followers on Instagram as @counseling4allseasons, where they regularly post and repost memes and educational material that is relatable, relevant and helpful for queer, trans, BIPOC, disabled and otherwise marginalized people. Lopez is known as a community leader who has been actively outspoken about issues that are intersectional with race, genocide, immigration, capitalism, patriarchy, queerness and mental healthcare.

At the time of the interview, Lopez was having a particularly hard day as it was the one month mark since the start of the fires that burned through Altadena neighborhoods.

“Today is a hard day. It’s the one month anniversary of when I evacuated Altadena,” said Lopez in an interview with LA Blade. “I feel really pissed today. I’m pissed that so many things happened that could have been prevented.

Lopez recalls that on Tuesday Jan. 7 when the Santa Ana winds were blowing the strongest, she received the notification about the power possibly being shut off, but during the time leading up to her evacuation, she recalls that the power was never shut off. All the other alerts she received came after the fire had already started.

As she was preparing to evacuate, she says that she was in communication with many of her friends and nearby neighbors.

“It was really confusing because I was texting a couple of people and some were saying they hadn’t received [a notification], while others had,” said Lopez.

At that point, their own instinct and intuition led them to make the ultimate decision to begin evacuating.

“Everything’s kind of a blur, but I started to just grab the dogs and cats,” they said. “So I started getting all of their supplies like their food, litter – everything they use.”

The aftermath of the fire on the property that Lopez rented a back house in (Photo courtesy of Melissa Lopez).

As soon as she was able to find short-term housing through AirBnB, she began organizing a group now led by a colleague of Lopez, to help people who had been directly affected and displaced by the Eaton Canyon fire. In the group, they discussed the experience of making the decision to take the evacuations seriously and begin gathering their belongings. She says she even felt ‘silly’ at some point, because she believed she would just be able to return the following day.

“What I tell people now is that I don’t care how silly you feel. I don’t care if you pack up half your house and feel silly about it. If your house ends up burning down, you will be so grateful for it because there are so many things I wish I would have taken.

Though Lopez says they don’t remember an exact timeline, they remember seeing the fire move in really fast and by the time she began evacuating it was complete chaos out on the main streets of Pasadena and Altadena because of the hundreds of people evacuating.

“Some of us had gotten notices, some of us warnings, some of us hadn’t,” Lopez recalls the confusing ordeal.

The smoke began to cloud the area so Lopez put her dogs into her car, but struggled to get her cats into a carrier and one of them was almost too scared to grab. She was able to make it out of the danger zone with all four of the members of ‘the coven,’ as she likes to call them.

Lopez gathered her coven and evacuated, saying goodbye to many of her belongings (Photo courtesy of Melissa Lopez).

“I had a friend who was going to take us in who lives in San Marino and driving there is basically a straight shot, but because it was so windy, some trees had fallen over and some of the [street] lights were out, so it was all really chaotic.”

Lopez believes that the community support she has received since the evacuations has gotten through the hardest parts of the experience. Mutual aid came to Lopez’s rescue during this difficult time. Navigating the resources and legal assistance was incredibly difficult because of the stress, trauma and grief she is still currently experiencing.

The Eaton Canyon fire burned through a large part of Altadena, an area that is predominantly and historically Black, Latinx and working-class.

“I think it’s important for folks to remember that showing up for community is actually very political,” said Lopez. “I want to encourage people to show up and even if you don’t know people, show up. Even if you don’t f*cking like people, show up.”

Lopez says they are very grateful for the community that showed up for them and that it is not only important to show up for this current disaster, but for everything marginalized communities are currently facing. They received many messages on IG from people offering their support in a variety of ways and that was all impactful to Lopez. They say that a lot of the support they received was from people they directly and personally knew, but a lot of it also came from people who were complete strangers.

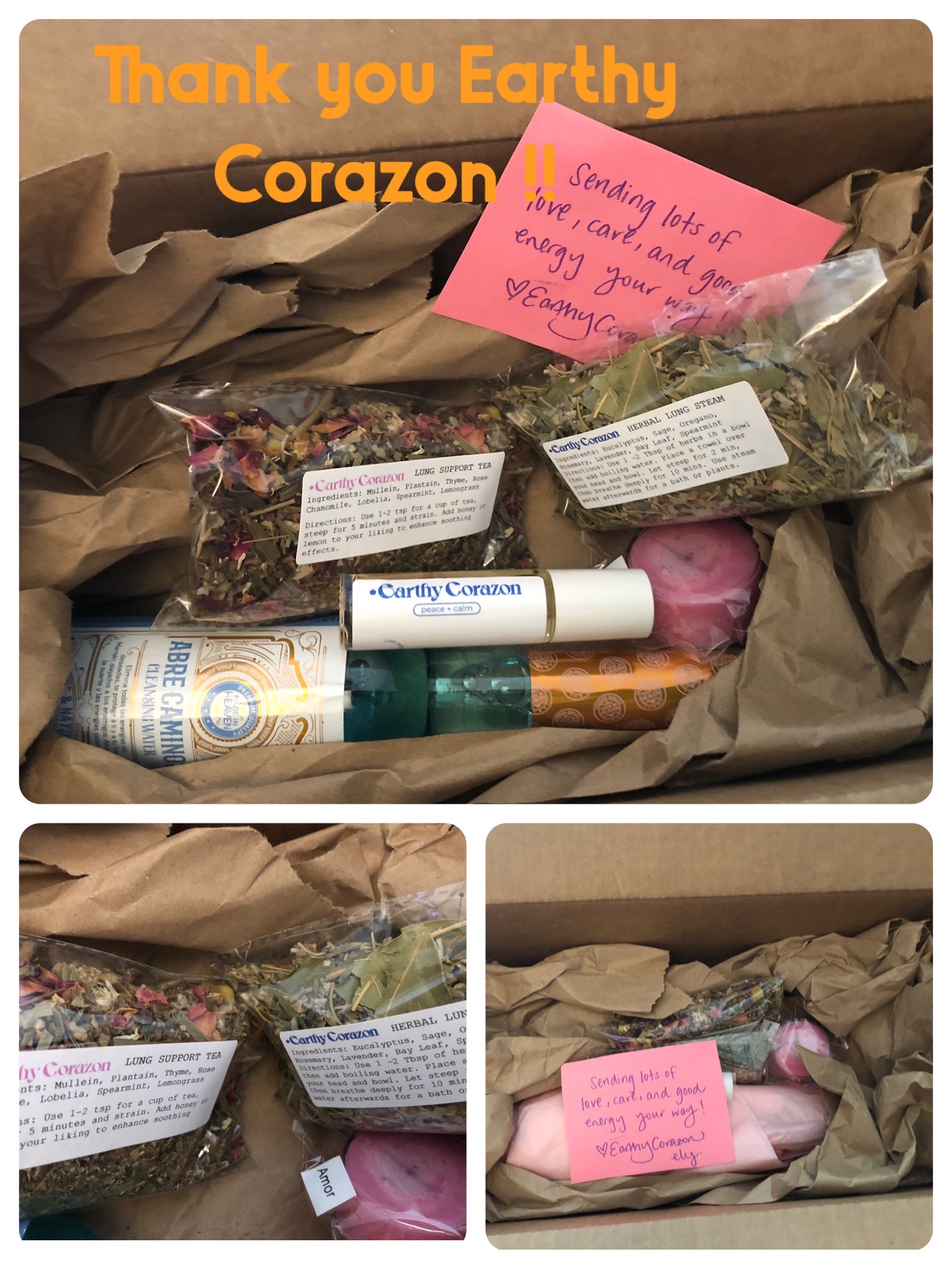

Lopez received holistic healing care packages from businesses like Earthy Corazón (Photo courtesy of Melissa Lopez).

In Lopez’s case, she was able to get her monthly rent for January and security deposit returned. She says she realizes that this is not the case for most people who are also navigating the aftermath of this disaster.

“I do want to highlight that I think tenants are having a really hard time because a lot of the resources and a lot of the support goes to homeowners and that is obviously a huge class issue,” said Lopez. “One thing I tell people now is get the f*cking renters insurance.”

The cause of the fire that took weeks to fully contain is still under investigation and many renters and homeowners await answers from insurance companies on their long path toward justice and permanent housing.

Features

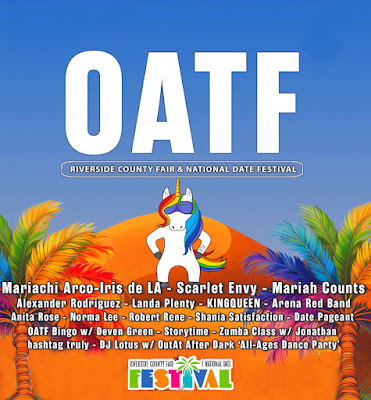

Out at the Fair Kicks Off Pride Season In SoCal

OATF continues to forge ahead with queer representation at local county fairs

Though the LGBTQ+ community is under attack day after day, queer organizations are not giving up the fight and instead are choosing to forge ahead with an even louder voice. Out At The Fair (OATF), is kicking off LGBTQ+ event season with a bang this week. Since it began in 2011, Out at the Fair has become the official LGBTQ+ event of the fair industry.

This year’s season starts at the Riverside County Fair & National Date Festival on Saturday, February 15th at 11 am. The Glam Show will feature a performance from Drag Race alum Scarlet Envy, who also appeared in the franchise’s All Stars and UK vs the World iterations. In addition to a number of California dates, OATF will appear in New Mexico, Oregon, and Alaska.

Simply put, it is a day the queer community gathers and takes over stages at your local country fair. This year Out At The Fair will appear in 13 cities in four states. The organization provides visibility for the LGBTQ+ community and creates an inclusive day at the fair with main stage music performances, drag queen story time for youth, community resources, health resources, giveaways, family-friendly activities, and a grand finale Glam Show featuring drag performances.

In this LA Blade exclusive, we chatted with Out At The Fair CEO and Founder William Zakrashek. Coming from a nightlife and DJ background, Will and his partners have kept OATF going strong, despite political and queer-phobic setbacks. The production team that travels on the road to each of the Fairs has been pretty much the same from its inception, a testament to the mission and professionalism of the organization.

OATF Founder William Zakrashek (Photo courtesy of OATF)

What was the inspiration to start Out at the Fair?

In 2011 we went to the San Diego County Fair and noticed there was no representation of the LGBTQ+ community so we just checked in on social media calling it the “Unofficial Gay Day.” Honestly, we didn’t think anything would come from it until the following year I got a message on social media asking if we were doing the gay day at the Fair again. We made an official Facebook event that year calling it the “Unofficial Gay Days” and were invited by Luis from Marketing at the SD Fair. They welcomed our full group to the fair, gave us pins, and took our photo. The following year I was invited to official SD Fair planning meetings and the vision of Out At The Fair came together and the rest is gay history now.

What have been your biggest challenges in producing these events?

Out at the Fair has to transform a conservative industry while changing the perception of the county fairs to our community. Because of the family-friendly nature and conservative backgrounds of Fairs, the queer community hasn’t felt like they can be themselves. I have to say with years of work, it is now. Every location with an OATF not only showcases our community to the full Fair but now welcomes the community to events at the Fair, 365 days a year. We hear from our Fair partners that the uptick in our community coming to the grounds beyond just county fair time had a huge increase.

Have you had any pushback from the straight, conservative community with OATF’s presence?

We have had the normal pushback that Prides get with protestors outside of the gates or rude verbiage from someone walking by our booth, but it has never been anything where we have felt threatened. We have a rule at the booth, if someone is video recording you and you do not feel comfortable, video record them back so we can handle it with the Fair teams. We work so closely with locations to make sure every year we get better and better at creating that safe space.