Movies

‘Firebird’ soars with tale of love during Cold War

A timely film exploring anti-LGBTQ oppression in Russia

Once in a while, current events and the release of a particular movie seem to coincide as if by fate. “Casablanca,” for instance, considered by its studio to be an unremarkable melodrama with limited box office appeal, was rushed into an early release to capitalize on the Allied invasion of North Africa, which took place in late 1942. The rest, of course, is history.

A similar twist of fateful timing surrounds “Firebird,” a UK-made gay romance set on a Soviet air base during the Cold War, as it goes into its official U.S. theatrical release on April 29. Based on a memoir by Sergey Fetisov, it’s a true story that not only resonates with the oppressive state of LGBTQ rights in modern-day Russia – a key factor in why the film was made in the first place – but that may pique the interest of American moviegoers thanks to the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“Firebird” – co-adapted for the screen by Estonian-born filmmaker Peeter Rebane and British actor Tom Prior, who direct and star, respectively – begins in the late 1970s as Sergey (Prior), a private in the Soviet Air Force with dreams of going to Moscow and becoming an actor, is eagerly counting down the days until the end of his military service. His life is suddenly changed irrevocably with the arrival of Roman (Oleg Zagorodinii), an ace fighter pilot newly stationed to the base; handsome, cultured, and approachable, the new officer immediately draws the attention of both Sergey and his close friend Luisa (Diana Pozharskaya), the Base Commander’s secretary – but it is with Sergey that he makes the deeper connection, and the two quickly become lovers.

Communist prohibitions against homosexuality are severe, however, especially for men in uniform, and even Ramon’s position of privilege is not enough to shield them from the ever-watchful eyes of their superiors. With his career and his freedom on the line, Roman initially breaks things off with Sergey, and even enters a sham marriage with the oblivious Luisa. But the love between them proves too strong to resist, and their star-crossed affair endures for years – despite the grim consequences they face should they be found out.

Tales of oppression such as this have never been in short supply in queer cinema. After all, movies, like any art, are an expression of real life, and therefore the unavoidable specter of the closet has loomed large over LGBTQ movies over the years. As a result, there are quite a few viewers out there who feel as if they have seen more than enough homophobia and heartbreak on their screens to last a lifetime. For such individuals, a movie like “Firebird” might be a hard sell.

Still, nostalgia is a powerful force, capable of bathing the past in a warm glow that softens harsh realities while making our happy memories even happier than we remember, and Rebane’s movie uses it to great advantage. The director infuses his lovingly recreated period setting not only with an eye-catching attention to detail, but with a lush and picturesque atmosphere that stimulates our fondest memories – or fantasies – as much as it does our appreciation for the retro Eastern Bloc aesthetic. The central romance stokes our idealized scenarios of illicit love at first sight, capturing that breathless blend of tenderness and red-hot sexual chemistry as well as the thrilling fear of discovery that somehow makes being together even more irresistible; we are plied, by scenes of furtive after-hours love-making and idyllic, sun-soaked scenes trysts by the sea, into believing that these handsome young lovers will somehow make it all work out.

The impossibility of their situation, of course, catches up to them eventually, and though the homophobia that surrounds them has been inescapable all along, it’s at this point the movie truly begins to explore its more subtle effects. Fear of it hangs over their relationship, and its poison spreads like a virus to anyone who becomes entangled in their life together; one of the film’s most powerful touches is the compassion it affords for Luisa, who may be an unknowing participant in the forced charade of their life together, but who suffers for it, nonetheless. It’s an all-too-rare reminder that repressive homophobia ruins heterosexual lives, too.

Indeed, compassion lies at the heart of “Firebird” and keeps it from being just another pretty-but-bittersweet gay love story from a bygone era. Rebane has said he was inspired to make the film by the resurgence of attacks against “basic human rights, equality and freedom” around the world, and particularly by the discrimination and repression experienced in many countries by LGBTQ individuals and families. In telling the real-life story of Sergey (who died in 2017, shortly after participating in extensive interviews with the filmmakers), he hoped to “foster more respect for one universal human right: to love and be loved.”

Now, with Russia’s aggression in Ukraine dominating world headlines, Rebane has reasserted his film’s purpose as a vehicle for raising awareness about the country’s “long history of persecuting LGBTQIA+ people and any of those voicing dissent to their authoritarian regime” by teaming with global advocacy group All Out, in support of their work in aiding queer refugees from Ukraine and fostering “meaningful dialogue” about Russia’s anti-LGBTQ policies.

Still, activist sentiment aside, “Firebird” is not political, but rather emphasizes the determination of a same-sex couple to exist, to survive despite suffering even within the most repressive of societies. In accomplishing that, it keeps its focus more on matters of the heart than on matters of state, something facilitated by its skillful cast – particularly Prior, whose appeal as Sergey runs far deeper than his youthful looks, and whose performance wears its heart on its sleeve without ever feeling overtly sentimental.

It’s perhaps because of this as much as its period setting that “Firebird” feels a bit like a throwback to a bygone era. Awash in stylish nostalgia, it seems like something seen from a distance, more felt than lived, more dreamed than experienced. That’s not a bad thing; it’s an aura that lends a calming effect, cushioning the emotional blows we know are sure to come, and gives the movie a sense of emotional balance that prevents it from becoming a tearjerker. At the same time, it also brings a sort of perfunctory quality to the events of the story, as though we are watching a carefully arranged row of dominoes fall, which occasionally threatens to undermine the impact of the draconian cultural oppression faced by its characters by reducing it to a mere plot device.

Nevertheless, it’s appropriate enough for a queer love story to feel a bit like a campy Hollywood classic, even when it has a political conscience. “Casablanca” raised awareness for the plight of refugees fleeing war-torn Europe, but it gave us Rick and Ilsa, too; and while it’s perhaps unlikely that “Firebird” will achieve the same status as that venerable masterpiece, its noble intentions and its unapologetic belief in love make it more than deserving of your attention.

Movies

Sexy small town secrets surface in twisty French ‘Misericordia’

A deliciously depraved story with finely orchestrated tension

The name Alain Guiraudie might not be familiar to most Americans, but if you mention “Stranger by the Lake,” fans of great cinema (and especially great queer cinema) are sure to recognize it immediately as the title of the French filmmaker’s most successful work to date.

The 2013 thriller, which earned a place in that year’s “Un Certain Regard” section of the Cannes Film Festival and went on to become an international success, mesmerized audiences with its tense and erotically charged tale of dangerous attraction between two cruisers at a gay beach, one of whom may or may not be a murderer. Taut, mysterious, and transgressively explicit, its Hitchcockian blend of suspense, romance, and provocative psychological exploration made for a dark but irresistibly sexy thrill ride that was a hit with both critics and audiences alike.

In the decade since, he’s continued to create masterful films in Europe, becoming a favorite not only at Cannes but other prestigious international festivals. His movies, each in their own way, have continued to elaborate on similar themes about the intertwined impulses of desire, fear, and violence, and his most recent work – “Misericordia,” which began a national rollout in U.S. theaters last weekend – is no exception; in fact, it draws all the familiar threads together to create something that feels like an answer to the questions he’s been raising throughout his career. To reach it, however, he concocts a story of small town secrets and hidden connections so twisted that it leaves a whole array of other questions in its wake.

It centers on Jérémie (Félix Kysyl), an unemployed baker who returns to the woodsy rustic village where he spent his youth for the funeral of his former boss and mentor. Welcomed into the dead man’s home by his widow, Martine (Catherine Frot), the visitor decides to extend his stay as he revisits his old home town and his memories. His lingering presence, however, triggers jealousy and suspicion from her son – and his own former school chum – Vincent (Jean-Baptiste Durand), who fears he has ulterior motives, while his sudden interest in another old acquaintance, Walter (David Ayala), only seems to make matters worse. It doesn’t take long before circumstances erupt into a violent confrontation, enmeshing Jérémie in a convoluted web of danger and deception that somehow seems rooted in the unspoken feelings and hidden relationships of his past.

The hard thing in writing about a movie like “Misericordia” is that there’s really not much one can reveal without spoiling some of its mysteries. To discuss its plot in detail, or even address some of the deeper issues that drive it, is nearly impossible without giving away too much. That’s because it’s a movie that, like “Stranger by the Lake” and much of Guiraudie’s other work, hinges as much on what we don’t know as what we do. Indeed, in its earlier scenes, we are unsure even of the relationships between its characters. We have a sense that Jérémie is perhaps a returning prodigal son, that Vincent might be his brother, or a former lover, or both, and that’s just stating the most obvious ambiguities. Some of these cloudy details are made clear, while others are not, though several implied probabilities emerge with a little skill at reading between the lines; it hardly matters, really, because as the story proceeds, new shocks and surprises come our way which create new mysteries to replace the others – and it’s all on shaky ground to begin with, because despite his status as the film’s de facto protagonist, we are never really sure what Jérémie’s real intentions are, let alone whether they are good or bad.

That’s not sloppy writing, though – it’s carefully crafted design. By keeping so much of the movie’s “backstory” shrouded in loaded silence, Guiraudie – who also wrote the screenplay – reminds us that we can never truly know what is in someone else’s head (or our own, for that matter), underscoring the inevitable risk that comes with any relationship – especially when our passions overcome our better judgment. It’s the same grim theme that was at the dark heart of “Stranger,” given less macabre treatment, perhaps, but nevertheless there to make us ponder just how far we are willing to place ourselves in danger for the sake of getting what – or who – we desire.

As for who desires what in “Misericordia,” that’s often as much of a mystery as everything else in this seemingly sleepy little village. Throughout the film, the sparks that fly between its people often carry mixed signals. Sex and hostility seem locked in an uncertain dance, and it’s as hard for the audience to know which will take the lead as it is for the characters – and if the conflicting tone of the subtext isn’t enough to make one wonder just how sexually adventurous (and fluid) these randy villagers really are beneath their polite and provincial exteriors, the unexpected liaisons that occur along the way should leave no doubt.

Yet for all its murky morality and guilty secrets, and despite its ominous motif of evil lurking behind a wholesome small-town surface, Guiraudie’s pastoral film noir goes beyond all that to find a surprisingly humane layer rising above it all, for which the town’s seemingly omnipresent priest (Jacques Develay) emerges to assert in the film’s third act – though to reveal more about that (or about him) would be one of those spoilers we like to avoid.

There’s a clue to be found, however, in the film’s very title, which in Catholic tradition refers to the merciful compassion of God for the suffering of humanity, but can be literally translated simply as “mercy.” Though it spends much of its time illuminating the sordid details of private human behavior, and though the journey it takes is often quite harrowing, “Misericordia” has an open heart for all of its broken, stunted, and even toxic characters; Guiraudie treats them not as heroes or villains, but as flawed, confused, and entirely relatable human beings. In the end, we may not know all of their dirty secrets, we feel like we know them – and in knowing them can find a share of that all-forgiving mercy for even the worst of them.

It’s worth mentioning that it’s also a movie with a lot of humor, brimming with comically absurd character moments that somehow remind us of our own foibles even as we laugh at theirs. The cast, led by the opaquely sincere Kysyl and the delicately provocative Frot, forge a perfect ensemble to create the playful-yet-gripping tone of ambiguity – moral, sexual, and otherwise – that’s essential in making Guiraudie’s sly and ultimately wise observations about humanity come across.

And come across they do – but what makes “Misericordia” truly resonate is that they never overshadow its deliciously depraved story, nor dilute the finely orchestrated tension his film maintains to keep your heart pounding as you take it all in.

To tell the truth, we already want to watch it again.

Movies

Stellar cast makes for campy fun in ‘The Parenting’

New horror comedy a clever, saucy piece of entertainment

If you’ve ever headed off for a dream getaway that turned out to be an AirBnB nightmare instead, you might be in the target audience for “The Parenting” – and if you also happen to be in a queer relationship and have had the experience of “meeting the parents,” then it was essentially made just for you.

Now streaming on Max, where it premiered on March 13, and helmed by veteran TV (“Looking,” “Minx”) and film (“The Skeleton Twins,” “Alex Strangelove”) director Craig Johnson from a screenplay by former “SNL” writer Kurt Sublette, it’s a very gay horror comedy in which a young couple goes through both of those excruciatingly relatable experiences at once. And for those who might be a bit squeamish about the horror elements, we can assure you without spoilers that the emphasis is definitely on the comedy side of this equation.

Set in upstate New York, it centers on a young gay couple – Josh (Brandon Flynn) and Rohan (Nik Dodani) – who are happily and obviously in love, and they are proud doggie daddies to prove it. In fact, they are so much in love that Rohan has booked a countryside house specifically to propose marriage, with the pretext of assembling both sets of their parents so that each of them can meet the other’s family for the very first time. They arrive at their rustic rental just in time for an encounter with their quirky-but-amusing host (Parker Posey), whose hints that the house may have a troubling history leave them snickering.

When their respective families arrive, things go predictably awry. Rohan’s adopted parents (Edie Falco, Brian Cox) are successful, sophisticated, and aloof; Josh’s folks (Lisa Kudrow, Dean Norris) are down-to-earth, unpretentious, and gregarious; to make things even more awkward, the couple’s BFF gal pal Sara (Vivian Bang) shows up uninvited, worried that Rohan’s secret engagement plan will go spectacularly wrong under the unpredictable circumstances. Those hiccups, and worse, begin to fray Josh and Rohan’s relationship at the edges, revealing previously unseen sides of each other that make them doubt their fitness as a couple – but they’re nothing compared to what happens when they discover that they’re also sharing the house with a 400-year-old paranormal entity, who has big plans of its own for the weekend after being trapped there alone for decades. To survive – and to save their marriage before it even happens – they must unite with each other and the rest of their feuding guests to defeat it, before it uses them to escape and wreak its evil will upon the world.

Drawing from a long tradition of “haunted house” tropes, “The Parenting” takes to heart its heritage in this campiest-of-all horror settings, from the gathering of antagonistic strangers that come together to confront its occult secrets to the macabre absurdity of its humor, much of which is achieved by juxtaposing the arcane with the banal as it filters its supernatural clichés through the familiar trappings of everyday modern life; secret spells can be found in WiFi passwords instead of ancient scrolls, the noisy disturbances of a poltergeist can be mistaken for unusually loud sex in the next room, and the shocking obscenities spewed from the mouth of a malevolent spectre can seem as mundane as the homophobic chatter of your Boomer uncle at the last family gathering.

At the same time, it’s a movie that treats its “hook” – the unpredictable clash of personalities that threatens to mar any first-time meeting with the family or friends of a new partner, so common an experience as to warrant a separate sub-genre of movies in itself – as something more than just an excuse to bring this particular group of characters together. The interpersonal politics and still-developing dynamics between each of the three couples centered by the plot are arguably more significant to the film’s purpose than the goofy details of its backstory, and it is only by navigating those treacherous waters that either of their objectives (combining families and conquering evil) can be met; even Sara, who represents the chosen family already shared by the movie’s two would-be grooms, has her place in the negotiations, underlining the perhaps-already-obvious parallels that can be drawn from a story about bridging our differences and rising above our egos to work together for the good of all.

Of course, most horror movies (including the comedic ones) operate with a similar reliance on subtext, serving to give them at least the suggestion of allegorical intent around some real-world issue or experience – but one of the key takeaways from “The Parenting” is how much more satisfyingly such narrative formulas can play when the movie in question assembles a cast of Grade-A actors to bring them to life, and this one – which brings together veteran scene-stealers Falco, Kudrow, Cox, Norris, and resurgent “it” girl Posey, adding another kooky characterization to a resume full of them – plays that as its winning card. They’re helped by Sublett’s just-intelligent-enough script, of course, which benefits from a refusal to take itself too seriously and delivers plenty of juicy opportunities for each of its actors to strut their stuff, including the hilarious Bang; but it’s their high-octane skills that bring it to life with just the right mix of farcical caricature and redeeming humanity. Heading the pack as the movie’s main couple, the exceptional talent and chemistry of Dodani and Flynn help them hold their own among the seasoned ensemble, and make it easy for us to be invested enough in their couplehood to root for them all the way through.

As for the horror, though Johnson’s movie plays mostly for laughs, it does give its otherworldly baddie a certain degree of dignity, even though his menace is mostly cartoonish. Indeed, at times the film is almost reminiscent of an edgier version of “Scooby-Doo”, which is part of its goofy charm, but its scarier moments have enough bite to leave reasonable doubt about the possibility of a happy ending. Even so, “The Parenting” likes its shocks to be ridiculous – it’s closer to “Beetlejuice” than to “The Shining” in tone – and anyone looking for a truly terrifying horror film won’t find it here.

What they will find is a brisk, clever, saucy, and yes, campy piece of entertainment that will keep you smiling almost all the way through its hour-and-a-half runtime, with the much-appreciated bonus of an endearing queer romance – and a refreshingly atypical one, at that – at its heart. And if watching it in our current political climate evokes yet another allegory in the mix, about the resurgence of an ancient hate during a gay couple’s bid for acceptance from their families, well maybe that’s where the horror comes in.

Movies

In LaBruce’s ‘The Visitor,’ the revolution will be sexualized

Exploring the treatment of ‘otherness’ in a society governed by xenophobia

If any form of artistic expression can be called the “front line” in the seemingly eternal war between free speech and censorship, it’s pornography.

In the U.S., ever since a 1957 Supreme Court ruling (Roth v. U.S.) made the legal distinction between “pornography” (protected speech) and “obscenity” (not protected speech), the debate has continued to stymie judicial efforts to find a standard to define where that line is drawn in a way that doesn’t arguably encroach on First Amendment rights – but legality aside, it’s clearly a matter of personal interpretation. If something an artist creates features material that depicts sexual behavior in a way that offends us (or doesn’t, for that matter), no law is going to change our mind.

That’s OK, of course, everyone has a right to their own tastes, even when it comes to sex. But in an age when the conservative urge to censor has been weaponized against anything that runs counter to their repressive social agenda, it’s easy to see how labeling something as too “indecent” to be lawfully expressed can be used as a political tactic. History is full of authoritarian power structures for whom censorship was used to silence – or even eliminate – anyone who dares to oppose them. That’s why history is also full of radical artists who make it a point to push the boundaries of what is “acceptable” creative expression and what is not.

Indeed, some of these artists see such cultural boundaries as just another way for a ruling power to enforce social conformity on its citizens, and consider the breaking of them not just a shock tactic but a revolutionary act – and if you’re a fan of pioneering “queercore” filmmaker Bruce LaBruce, then you know that’s a description that fits him well.

LaBruce, a Canadian who rose to underground prominence as a writer and editor of queer punk zines in the ‘80s before establishing himself as a photographer and filmmaker in the “Queercore” movement, has never been deterred by cultural boundaries. His movies – from the grit of his gay trick-turning comedy “Hustler White,” through the slick pornographic horror of “LA Zombie,” to the taboo-skewering sophistication of his twin-cest romance “St. Narcisse” – have unapologetically featured explicit depictions of what some might call “deviant” sex. Other films, like the radical queer terrorist saga “The Raspberry Reich” and the radical feminist terrorist saga “The Misandrists,” have been more overtly political, offering savagely ludicrous observations about extremist ideologies and the volatile power dynamics of sex and gender that operate without regard for ideologies at all. Through all of his work, a cinematic milieu has emerged that exists somewhere between the surreal iconoclasm of queer Italian provocateur Pier Paolo Pasolini and the monstrous camp sensibility of John Waters, tied together with an eye for arresting pop art visuals and a flair for showmanship that makes it all feel like a really trashy – and therefore really good – exploitation film.

In his latest work, he brings all those elements together for a reworking of Pasolini’s 1968 “Teorema,” in which an otherworldly stranger enters the life of an upper class Milanese family and seduces them, one by one. In “The Visitor,” Pasolini’s Milan becomes LaBruce’s London, and the stranger becomes an impressively beautiful, sexually fluid alien refugee (burlesque performer Bishop Black) who arrives in a suitcase floating on the Thames. Insinuating himself into the home of a wealthy family with the help of the maid (Luca Federici), who passes him off as her nephew, he exerts an electrifying magnetism that quickly fascinates everyone who lives there. Honing in on their repressed appetites, he has clandestine sex with each in turn – Maid, Mother (Amy Kingsmill), Daughter (Ray Filar), Son (Kurtis Lincoln), and Father (Macklin Kowal) – before engaging in a incestuous pansexual orgy with them all. When the houseguest departs as abruptly as he arrived, the household is left with its bourgeois pretensions shattered and its carnal desires exposed, each of them forced to deal with the consequences for themselves.

Marked perhaps more directly than LaBruce’s other work with direct nods to his influences, the film is dedicated to Pasolini himself, in addition to numerous visual references throughout which further underscore the “meta-ness” of paying homage to the director in a remake of one of his own films; there are just as many call-backs to Waters, most visibly in some of the costume choices and the gender-queered depiction of some of its characters, but just as obviously through the movie’s “guerilla filmmaking” style and its gleefully transgressive shock tactics – particularly a dinner banquet sequence early on which leisurely rubs our noses in a few particularly dank taboos. There are also glimpses and echoes of Hitchcock, Kubrick, Lynch, and other less controversial (but no less challenging) filmmakers whose works have pushed many of the same boundaries from behind the veneer of mainstream respectability.

Despite all of these tributes, however, “The Visitor” is pure LaBruce. Celebratory in its depravity and unflinching in its fully pornographic (and unsimulated) depictions of sex, from the blissfully erotic to grotesquely bestial, it seems determined to fight stigma with saturation – or at least, to push the buttons of any prudes who happen to wander into the theater by mistake – while mocking the fears and judgments that feed the stigmas in the first place.

That doesn’t mean it’s all fluid-drenched sex and unfettered perversion; like Pasolini and his other idols, LaBruce is a deeply intellectual filmmaker, and there’s a deeper thread that runs throughout to deliver an always-relevant message which feels especially relevant right now: the treatment of “otherness” in a society governed by homogeny, conformity, and xenophobia. “The Visitor” even opens with a voiceover radio announcer lamenting the influx of “brutes” into the country, as suitcases bearing identical immigrants (all played by Black) appear across London, and it is by connecting to the hidden “other” in each of his conquests that our de facto protagonist draws them in.

LaBruce doesn’t just make these observations, however; he also offers a solution (of sorts) that matches his fervor for revolution – one in which the corruption of the ruling class serves as an equalizing force. In each of the Visitor’s extended sexual episodes with the various family members, the director busts out yet another signature move by flashing propaganda-style slogans – “Give Peace of Ass a Chance,” “Go Homo,” and “Join the New Sexual World Order” are just a few colorful examples – that are as heartfelt as they are hilarious. In LaBruce’s revolution, the path to freedom is laid one fuck at a time, and it’s somehow beautiful – despite the inevitable existential gloom that hovers over it all.

Obviously, “The Visitor” is not for all tastes. But if you’re a Blade reader, chances are your interest will be piqued – and if that’s the case, then welcome to the revolution. We need all the soldiers we can get.

“The Visitor” is now playing in New York and debuts in Los Angeles March 14, and will screen at roadshow engagements in cities across the U.S. Information on dates, cities, and venues (along with tickets) is available at thevisitor.film/.

Movies

‘John Cranko’ tells story of famed LGBTQ ballet choreographer

South African arrived in Germany in 1960

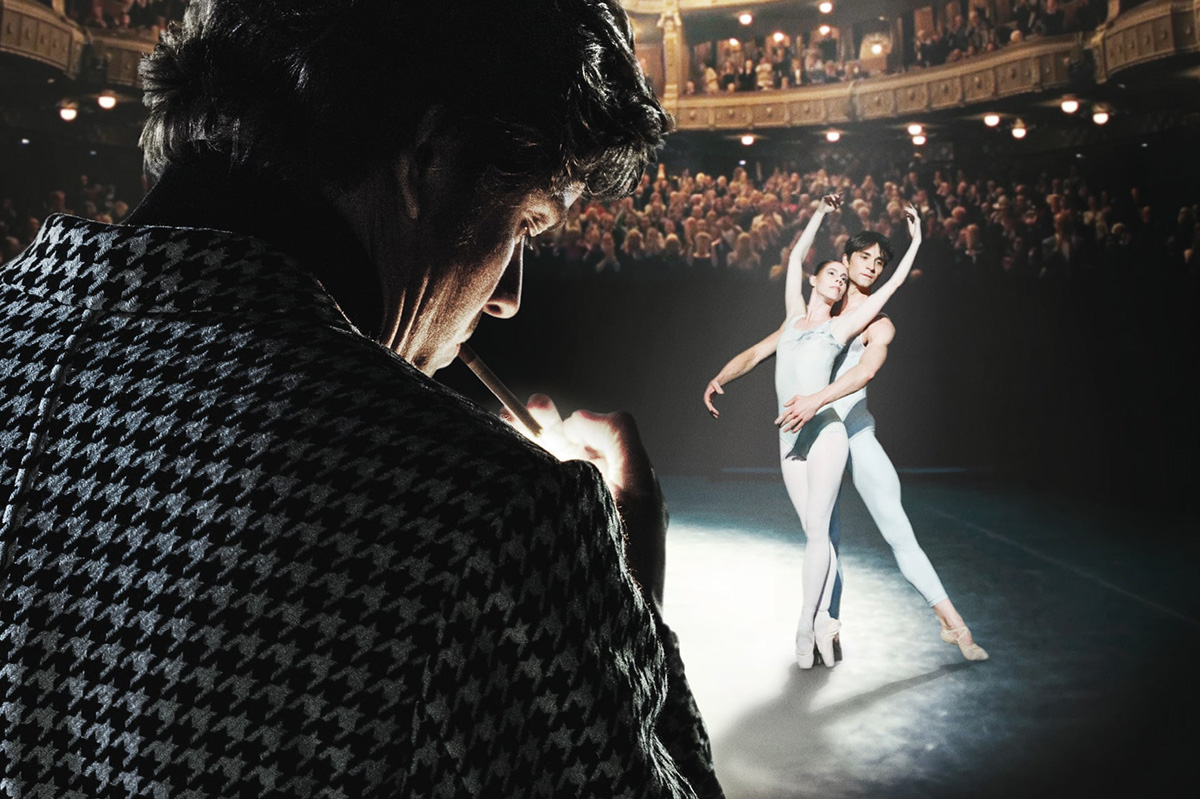

One of the highlights of the Palm Springs Film Festival was Joachim A. Lang’s beautiful German-language film, “John Cranko,” which tells the true story of the famed LGBTQ ballet choreographer.

The film follows the South African-born Cranko, (played by Sam Riley) as he arrives in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1960, to be guest choreographer for the city’s ballet company after a very public scandal: his job at London’s Sadler’s Wells Ballet abruptly ended after he was prosecuted for committing a homosexual act in a public place.

In the relaxed city of Stuttgart, Cranko is able to find refuge from his past and is embraced despite his unique lifestyle. He quickly rises to become the ballet director and a favorite of the audience, dedicating himself fully to his art and a vibrant social life. He engages in affairs, faces personal setbacks and deep crises, runs his office from the theater canteen, and affectionately refers to his company as “his children.”

Lang’s perspective

Cranko was a fascinating enigma to capture on screen, with a complicated, often manic, personality. Loved by his gifted dancers, he was extremely passionate about ballet, and creative in his artistry, yet cantankerous at times, often dealing with depression and a heavy alcohol intake.

Over the years, Lang had “intensive conversations” with companions and friends of Cranko, which greatly helped him with the script.

“I talked with Marcia Haydee, the great ballerina of the 20th century; Birgit Keil, equally famous; costume designer Jürgen Rose; and ballet dancer Vladimir Klos,” Lang told the Los Angeles Blade. “And especially ballet dancer Reid Anderson and administrator of the Stuttgart Ballet and holder of the rights to John Cranko’s ballets, Dieter Gräfe, both of whom lived with John Cranko.”

Many of them were on board when sadly, Cranko died somewhere over the Atlantic between America and Europe on the flight back from a guest performance of his ballet company in New York, in 1973, at the age of 45.

For Lang, the biggest challenge was to realize his goal of making one of the first “real” ballet films.

“A film that is really about this art–the film wants to be more than a biopic, it is an attempt to capture the soul of dance by portraying the life and work of this genius. It is a film about art and reality, it is about us humans, the time we have left and what drives us, it is about the great themes of being human, the longing for love, life and dying. It is a tribute to art and to the people who make it.”

Riley’s portrayal

Thefilm delves into the delicate nature of a lonely, fragile soul searching for love and recognition. It’s no wonder Riley, known for his mesmerizing role in “Control,” where he played Joy Division’s Ian Curtis, as well as “Rebecca” and “Maleficent,” is absolute perfection in the role.

“Sam Riley is one of the best actors,” acknowledged Lang. “I knew right away that only he could do it so well. I sent him the script. We met for an hour in a hotel in Berlin. It was clear then that we belonged together. He was world class. The greatest praise for him was when I showed the film to Cranko’s companions, they said: ‘John is back!’”

With so much archival footage, Riley was able to deeply immerse himself in the character.

“With John, there’s quite a lot of material, the (Stuttgart) Ballet had an archive of stuff, so I got all of his old performances with the original cast. And there was quite a lot of footage of him at work, choreographing and directing. I watched as much as they had. Rather than mimic it, you just try and absorb it somehow.”

Because ‘ballet is such a universal thing,” Riley really hopes the film can do well outside of Germany.

“What I found most inspirational about being in the film was something that I wasn’t really expecting. I think, like a lot of guys, I had grown up with a sort of unconscious prejudice against ballet. I’d never actually been to see one my whole life, until I went to be a part of this. I just assumed it was something not for me. I like rock and roll music and movies and things.”

But it was in watching the young dancers rehearse that touched Riley’s heart.

“Realizing that they’ve been dedicating their lives to this art form since they were little children, the effort that they put into it every day, the work ethic, and that something that still exists today, just a pure dedication to something — that’s beautiful … They are performing for the love of it. And it moved me every day, really, watching them do it. Every scene, they really throw absolutely everything into it. They were completely exhausted. And it was really inspiring.”

Movies

A cat and its comrades ride to adventure in breathtaking ‘Flow’

Latvian filmmaker Gints Zilbalodis directs animated fantasy adventure

Sometimes, life changes overnight, and there’s nothing to do but be swept away by it, trying to navigate its currents with nothing to help you but sheer instinct and the will to survive.

Sound familiar? It should; most lives are at some point met with the challenge of facing a new personal reality when the old one unexpectedly ceases to exist. Losing a job, a home, a relationship: any of these experiences require us to adapt, often on the fly; well-laid plans fall by the wayside and the only thing that matters is surviving to meet a new challenge tomorrow.

When such catastrophes are communal, national, or even global, the stability of existence can be erased so completely that adaptation feels nearly impossible; the “hits” just keep on coming, and we’re left reeling in a constant state of panicked uncertainty. That might sound familiar, too.

If so, you likely realize that there’s little comfort to be found in most of the entertainments we seek for distraction, outside of the temporary respite provided by thinking about something else for a while — but there are some entertainments that can work on us in a deeper way, too, and perhaps provide us with something that feels like hope, even when we know there is no chance of returning to the world we once knew.

“Flow” is just such an entertainment.

Directed by Latvian filmmaker Gints Zilbalodis from a screenplay co-written with Matīss Kaža, this independently-produced, five-and-a-half-year-in-the-making animated fantasy adventure has become one of the most acclaimed films of 2024; debuting at Cannes in the non-competitive “Un Certain Regard” section, it won raves from international reviewers and went on to claim yearly “best of” honors from numerous critics’ organizations and film award bodies, including the Golden Globes and the National Board of Review. Now nominated not only for the Academy’s Best Animated Feature award but as Best International Feature (only the third animated movie to accomplish that feat) as well, it stands as the odds-on favorite to take home at least one of those Oscars, and possibly even both — and once seen, it’s hard to dissent from that assessment.

Set in an unspecified time and an unknown, richly forested place, it centers its narrative — which begins with breathtaking quickness, almost from the opening frames of the film — on a small-ish charcoal grey cat, who wakes from its slumber to find its home rapidly disappearing under a rising tide of water. Trying to stay ahead of the flood, it finds a lifeline when it discovers an abandoned sailboat, adrift on the waves, and seeks safety on board; but the cat is not the only refugee here, and with an unlikely group of other animals — a dog, a capybara, a lemur, and a secretary bird — sharing the ride, the plucky feline must forge alliances with (and between) each of its shipmates if any of them are to avoid a seemingly apocalyptic fate. Faced with setbacks and challenges at every turn, the crew of unlikely comrades learns to cooperate out of shared necessity — but will it be enough to keep the uncontrollable waters that surround them from becoming their final oblivion?

With no human presence in the movie — though the implication that it once existed, accompanied by the inevitable suspicion that climate change is behind the mysterious flood, is ominously delivered through the monumental ruined structures and broken relics it has seemingly left behind — the story unfolds without a word of dialogue, a narrative chain of events that keeps us ever-focused on the “now.” The non-verbal vocalizations of its characters (each provided by authentic animal sounds rather than human impersonation) help to convey their relationships with clarity, but it’s the visual evocation of their sensory experiences — of being trapped and at the mercy of the elements, of making an unexpected connection with another being, of enjoying a simple pleasure like a soft place to sleep — that fuels this remarkable exploration of physical existence at its most raw and vulnerable. We have no way of knowing what has happened, no way of imagining what is yet to come, but such questions fade quickly into irrelevance as the story carries our attention from the immediacy of one moment into the next.

Accentuating this in-the-moment flow of “Flow”— for if ever a film title could be said to summarize its style, it is surely this one — is its eye-absorbing visual beauty, rendered via the open-sourced software Blender to provide an aesthetic which matches the material. These realistically-drawn animals come vividly to life against a backdrop that captures a deep connection to nature, accented with the surreal intrusions of human influence and a certain appreciation for the colorful beauty of the world around us, even at its most untamed, which hints at an indefinable mysticism; and when the story begins to transcend the expected borders of its meticulously-crafted realism, the animation takes us there so easily that we scarcely notice it has happened.

Yet transcend it does, and in so doing becomes something greater than a humble adventure tale. As the animal companions progress in their journey toward hoped-for safety, the remnants of human existence become more weathered, more ancient, and less recognizable; the natural landscape through which they are carried begins to be transformed, rendered in a more mythic light by the clash of elemental forces swirling around them and the strange encounters with other creatures that occur along their way. Whatever world this may have been, it seems rapidly to be dissolving into a cosmos where the forms of the past are being reconfigured into something new — and the band of travelers, both witness to and participants in this process, cannot help but be reconfigured, too.

We can’t explain that further without spoilers, but we can tell you that it includes the cat’s ability to ignore its solitary instincts and natural mistrust of its comrades in order to form a diverse (yes, we said it) and cooperative team. It also involves learning to let go of things that can no longer help, to be open to new possibilities that might, and perhaps most importantly, to surrender without fear to the “flow” and trust that it will eventually take you where you need to go, as long as you can manage to stay afloat until you get there.

Zilbalodis’s film is an immersive ride, full of visceral and frequently harrowing moments that may produce some anxiety (especially for those who hate seeing animals in peril) and conceptual shifts that may challenge your expectations — but it is a ride well worth taking. More than merely a fantastical “Noah’s Ark” fable reimagined for an environmentally conscious age, it just might offer the timely catharsis many of us need to confront our unknowable future with a renewed sense of possibility.

“Flow” begins streaming on Max on Feb. 14.

Movies

Animated Oscar contender ‘Snail’ a bittersweet delight

Showcasing the power of kindness to help us endure difficult times

Even in a time when it has been well established that an animated film is not necessarily meant for children, you might expect one with the title “Memoir of a Snail” to be something soft, sweet, and whimsical enough to be suitable for even the youngest of toddlers – but you can’t judge a film by its title, any more than you can a book by its cover.

One of 2024’s most well-received films, animated or otherwise, this deceptively adorable feature from Australian animator Adam Elliott certainly fits part of the above description (the “whimsical” part), but it could only be considered a children’s movie by someone who still thinks “cartoons” are for kids. Elliott – whose 2003 film “Harvie Krumpet” won the Oscar for Best Animated Short – is a filmmaker who uses animation (or more specifically, stop-motion “claymation”) to tell semi-autobiographical stories, often about characters based on his own family and friends, and while his visual style might be cute enough to engage your toddler, the content of his narratives is unmistakably tailored for adults.

In this case, that narrative is centered on – and told in flashback by – one Grace Prudel (voiced as an adult by “Succession” star Sarah Snook, and as a child by Charlotte Belsey and Agnes Davison), a girl who grows up in 1970s Melbourne with a twin brother named Gilbert (Mason Litsos/Kodi Smit-McPhee) under the care of their father, a former French animator (Dominique Pinon) with a fondness for roller coasters. When he dies and leaves them without support, the deeply bonded Grace and Gilbert are taken into the foster system and sent to live with families on opposite sides of the country. Grace, whose “swinger” foster parents often leave her on her own, struggles with isolation and loneliness, while Gilbert suffers under the tyrannical rule of a fundamentalist religious couple who exploit all their children as free labor.

Eventually, Grace crosses paths with Pinky (Jacki Weaver), an elderly free spirit who takes on the role of mentor and helps her endure a number of hardships, including a disastrous wedding engagement and her continued separation from Gilbert; depressed, overweight, and increasingly seeking refuge with her collections of snails, romance novels, and guinea pigs – all of which serve as both consolation and distraction from her seemingly impossible dream of following in her father’s footsteps to make animated films – it is her bond with Pinky that may finally provide her with the lifeline to keep her hope alive.

Striking a delicate balance between sentiment and savvy, Elliott’s film – his first feature effort since 2009’s “Mary and Max” – bridges the gap expertly with just enough satirical exaggeration to avoid being maudlin, yet keeps its eye on the redemptive prize (despite the occasional Dickensian twist) by treating Grace with the kind of empathy that can only be achieved by putting the audience completely into her shoes. Without spoilers, we watch as she goes through multiple quirky-yet-relatable setbacks, reinforcing the connection with our own inner misfit by conjuring familiar (and potentially unifying) feelings of inadequacy and leading us, inevitably, to forgive ourselves for our perceived shortcomings.

Visually, “Memoir of a Snail” evokes memories of many other stop-motion efforts, contrasting the inherent “cuteness” of its style with the less-comforting content of its storyline. Resembling a tried-and-true “Wallace and Gromit” film (such as fellow Oscar-nominee “Vengeance Most Foul”) but decidedly more focused on the inner lives of its characters, it blends and contrasts a familiar and traditional form with an emotional honesty that disarms our cynicism. Mixed with its comforting whimsy is an acknowledgement of life’s dark corners, a frank awareness that, sometimes, loss and sorrow happen and there’s nothing to be done but to go through them – there are no fantastical inventions to ease Grace’s path, no tongue-in-cheek capers that can set things right and restore her world to some kind of happy status quo; like the rest of us, she must work through the darkness not to get back to the way things were, but to arrive at a place where new things are possible – where the grief and sorrow that are inevitably woven into our life can be weathered and overcome, even if they can’t be avoided.

As to that grief and sorrow, “Memoir of a Snail” touches on the universal; Grace’s struggles with loss and loneliness, the disappointments, humiliations, and outright betrayals she confronts, all hit close to home – the loss of loved ones, the loneliness of not fitting in, the trauma of being bullied and abused – and there are no easy answers to getting through them.

Yet melancholy as its tone may often feel, Elliott’s movie defies its own gravity with a wicked sense of humor and a sharp knack for commentary on the quirks and foibles of human behavior. Despite the grimness into which it sometimes must descend – which includes the depiction of shock treatment used for “conversion therapy” by Gilbert’s homophobic foster family – it manages to maintain a light-hearted attitude, buoyed by a keen (and often ironic) sense of humor and an embrace of the inescapable absurdities of life, and emerge not only with acceptance but with hope – with a little help, that is, from our friends.

It’s this message that infuses “Memoir” with such a sense of humanity; it is through the special bonds she finds that Grace endures – and not only the ones she shares with her beloved snails. The heart of the movie beats through her friendship with Pinky, a fellow “misfit” with the wisdom and kindness to renew her faith in life, and it’s that warmth and humanity that takes a tale of hardship and emotional suffering and turns it into one of the year’s most delightful movies.

Visually lovely, with an array of memorable voice performances and a delicious balance of humor ranging from silly to the macabre, “Memoir of a Snail” may not have the Disney appeal – nor the subject matter – to make it a good choice for children, but it has the candor and willingness to explore the darker places in our lives, the “sacred wounds” that give our lives meaning, and the power of love to keep us in the light.

Nominated for the Best Animated Feature Oscar, Elliott’s film is now streaming via multiple VOD platforms – and as much, if not more, worth your attention as any of the live action films competing in the other categories. After all, a movie about the power of kindness to help us endure difficult times is something most of us could probably use, right about now.

Movies

Awards favorite ‘The Brutalist’ worthy of the acclaim

Brody’s performance a master class in understated emotional expression

If there’s anything Hollywood loves – during “Awards Season” at least – it’s a good old-fashioned epic.

From “Gone With the Wind” to “Ben-Hur” to “The Godfather” and beyond, the film industry has always favored “big” movies when it comes to doling out its annual accolades, in part because awards equate to more public interest (and therefore more revenue) for films that might not otherwise grab enough attention to earn back their massive budgets. Yet, profit motive aside, such movies exude the kind of monumental grandeur that has come to be seen as the pinnacle of filmmaking craft, a perfect blend of art and entertainment that represents Hollywood at its finest and most iconic. It only makes sense that the people whose life is devoted to making movies would want to celebrate something that lives up to that ideal, especially when it also seems to reflect the cultural climate of its time.

That’s good news for “The Brutalist,” which has been buzzed – for months now – as the front-runner for all the Best Picture awards and seems to have proven its inevitability with its win of the Best Motion Picture Drama prize at this week’s Golden Globes. It meets all the requirements for an epic prestige picture: a sweeping plot, containing a nebula of currently relevant thematic ideas, but with an iconic historical period as its backdrop; monumental settings, spectacular locations, and impeccably designed costumes; an acclaimed actor giving a tour-de-force performance at the head of a proverbial “cast of thousands” and a runtime long enough to necessitate an intermission. Add the fact that it comes with an array of already-bestowed prizes from some of the most prestigious film festivals in the world, not to mention high placement on most of the year’s prominent “10 best” lists, and its predicted victory charge through the rest of the awards gauntlet looks likely to be a sure bet.

That assessment might seem glib, even cynical, but it’s no reflection on the movie. On the contrary, “The Brutalist” stands out above the rest of the crop not because of the hype, but because of its cinematic excellence, and that is precisely what has made it such an attractive awards candidate.

Spanning several decades across the mid-20th century, it’s the saga of László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a Hungarian Jewish refugee – once a young rising star on the European architecture scene – who seeks a new life in America after being liberated from a Nazi concentration camp. Reuniting with his already-Americanized cousin (Alessandro Nivola), who now owns a furniture business in New York, he offers his Bauhaus-educated expertise in exchange for a place to stay, leading to a fortuitous connection with a wealthy industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) who becomes enamored with his work. The resulting commission not only allows him to design and begin construction on a spectacular new masterpiece, but to facilitate the emigration of his beloved wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) – from whom he had been separated during the war – and his orphaned niece Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy).

Things are never easy for an immigrant, however, and unanticipated setbacks on an ambitious project for his mercurial new patron – possibly connected to a “functional” heroin habit that has grown increasingly difficult to balance with his professional life – soon lead to one reversal of fortune after another. It will take years before László is finally given the chance to complete his dream project, but even then the volatile affections of Van Buren threaten to thwart his ambitions before they can reach fruition.

It’s difficult to offer a synopsis that effectively sums up the powers of this film’s singular combination of pseudo-historical gravitas (the “pseudo” in this case means “fictionalized,” not “untruthful”) and coldly aloof observational commentary about the truth behind the so-called “American Dream”; director Brady Corbet unfolds his boldly countercultural narrative, in which the wealth and power of a privileged class that holds sway over the destiny of immigrants and outsiders is allegorically portrayed through the relationship between a visionary artist and the oligarch who ultimately wants nothing more than to exploit him. It’s an unmistakably political perspective that shines through that lens, and one that feels eerily apt in a time when even the greatest expressions of our humanity are granted value only so far as they serve the interests – and feed the egos – of the ruling power elite, and marginalized outsiders are “tolerated” only as long as they are useful.

In the intricately woven screenplay by Corbet and writing partner Mona Fastvold, these ideas run throughout the story of László’s American experience like the streaks of color in a slab of fine marble, turning “The Brutalist” into an anti-fascist parable through the personal stories of its characters. The portrait it paints of American classism, racism, anti-Semitism and sexism – all perhaps most boldly personified by Van Buren’s arrogantly boorish son (Joe Alwyn) – is not an attractive one; and though it grants us historical distance to make its observations, it is impossible not to see both the ominous connections that can be made to our current era and the true character of an American history in which “greatness” only existed for those with the money to buy it. The result is an eloquent piece of filmmaking that manages to “speak truth to power” through the details of its narrative without lofty speeches (mostly) or other contrivances to highlight its arguments – though admittedly, the broad strokes with which it crafts some of its more unpleasant characters occasionally feel like not-so-subtle Hollywood-style manipulation.

Ultimately, of course, what gives Corbet’s movie its real power is its size. Like the architectural style embraced by its title character, “The Brutalist” is monumental, a construction of high ceilings and ornate furnishings that is somehow streamlined into a minimalist, functional whole. Superbly shot by cinematographer Lol Crawley in a nostalgic VistaVision screen ratio that demands viewing on the big screen, it boasts a bold visual aesthetic rarely attempted by modern films, further suiting the scale of the statement it makes.

Finally, though, it’s Brody’s outstanding performance that drives the film, a master class in understated emotional expression that reveals a complex landscape of pain and passion through nuance rather than bombast. Jones is also superb as his wife, every bit his intellectual equal and exuding strength despite being wheelchair bound, and Pearce delivers a career-highlight turn as Van Buren, capturing both his confident charisma and terrifying rage while still giving glimpses of the hidden passions that lurk below them – though to say more about that might constitute a spoiler.

There’s no denying that “The Brutalist” is a superb movie, and one that feels as capable of standing the test of time as one of its protagonist’s structures. Make no mistake, though, it’s no crowd-pleaser; non-cinema buffs may be daunted by its combination of extreme length and leisurely pace, and while it has its moments of uplift, it can also be grim and melancholy. For those with the stamina for it, however, it’s a movie that enfolds you completely, and holds your interest for each of its 200 minutes.

Movies

A star performance shines at the heart of ‘Emilia Pérez’

A breathtaking high point in trans visibility on the big screen

If all you know about “Emilia Pérez” going into it is that it began life as the libretto for an opera, it might better prepare you than any mere description of its plot.

That’s because veteran French writer/director Jacques Audiard’s latest work (which premiered at Cannes in 2024 to a lengthy standing ovation and is now streaming on Netflix) is a larger-than-life affair fueled by yearning, passion, irony and fate. Its twists and turns might seem like outlandish melodrama but for its focus on the nuanced inner lives of its characters; that it accomplishes this focus through music – like opera – feels almost a mere coincidence of form, because the tale it unfolds would be as operatic as “Tosca” even if there were not a single note of music on the soundtrack.

There is plenty of music, though. In fact, though it’s a movie for which the overused description “genre-defying” could easily have been invented, “Emilia Pérez” can safely be called a musical; it’s driven through songs by French avant garde vocalist Camille and a score by composer Clément Duco, performed onscreen by its cast and accompanied by visually stunning choreographed sequences by Damien Jalet throughout the story – and it’s quite a story.

Using a gifted but struggling lawyer – Rita (Zoe Saldaña) – as an entry point for the audience, Audiard takes us with her into the dark underworld of a Mexican drug empire when she is summoned to meet with a powerful cartel kingpin named “Manitas” (Karla Sofía Gascón), who is seeking a gender reassignment surgery and is both willing and able to pay her a life-changing sum of money to arrange it. It’s an offer she can’t refuse (yes, literally), and she succeeds in securing a doctor (Mark Inavir) who – after being convinced of the patient’s sincerity – agrees to do the job; she also handles the awkward business of convincing her employer’s wife Jessi (Selena Gomez) and their children of “his” death and moving them to Switzerland to protect them from former rivals who might target them.

That saga, which might easily be enough to fuel an entire film by itself, is only the first chapter of an epic journey which then jumps forward several years to find Rita surprised by the reappearance of Manitas – now comfortably living as the Emilia of the title – and her new desire to reunite with her children. She decides to help, beginning a genuine friendship with the former drug lord which eventually blossoms into a redemptive campaign to help the families of missing loved ones lost to cartel violence – even as the emotional baggage of a carefully-hidden past (and the ghosts of a former identity still struggling for dominance) begin to reassert themselves within the authentic new life Emilia has tried to build, threatening to drag both women down in a final, desperate power play that could cost them both their lives.

Almost literary in the grand scale of its ambition, “Emilia Pérez” packs so much into its narrative that it feels much longer than its two-and-a-quarter hour runtime – but not because it drags. On the contrary, its plot advances quickly, thanks in part to the powerful blend of musical and cinematic storytelling; it’s the richness and density of its emotional terrain, marked by both the dramatic landscapes of our primal urges and the delicate beauty of our noblest aspirations, that makes it seem epic, a sense of containing so much that it requires more space in our mind, perhaps, than it does time to convey it all. Audiard deftly uses broad strokes to heighten our experience, blending them with a feather-light touch that allows the subtleties of its “colors” to emerge with equal clarity, and draws on a mastery of the medium gained both from growing up as the son of a filmmaker and a nearly four-decade career behind the camera in his own right. The result is a near-kaleidoscopic modern-day fable – steeped in the dappled beauty of Paul Guilhaume’s cinematography – that remains firmly tethered to humanity, even as the story moves toward a denouement that feels almost mythic in stature.

While Audiard is undeniably the unifying force which allows “Emilia Pérez” to achieve its heights, it’s also a film whose success or failure hinges on its key performers – with the title role, in all its contradictory grandeur, standing out as the essential lynch pin. Gascón fills Emilia’s shoes magnificently, not only proving what is possible when a trans actor is allowed to bring the full authenticity of their lived experience to a trans character, but revealing a breathtaking talent that transcends the shallow irrelevance of gender distinctions when it comes to valuing an artist’s gifts. Already making history by earning Gascón the first Golden Globe nomination for a Best Leading Actress award, it’s a performance that feels like a landmark from her first appearance – as the pre-transition Manitas, a gold grille on his teeth and a coiled menace in his gruff-but-intelligent voice – and only enthralls us more as she takes the character through her epic journey.

Though she is the movie’s natural anchor, she’s joined by a trio of female co-stars that match her every step of the way. Saldaña, given top billing as the film’s biggest “name,” earns that distinction with an intelligent, vulnerable performance that showcases her own skills yet never threatens to overshadow Gascón’s, and Gomez steps confidently into her role while still projecting a nervous fragility that keeps the character from losing our empathy. Rounding out the ensemble is Adriana Paz, as a woman who opens up Emilia to the unexpected possibility of love in her life. Together, these four performers were awarded Best Actress Prize as an ensemble at Cannes, where the film also won the festival’s prestigious Grand Jury Prize.

Since that auspicious debut, “Emilia Pérez” has gathered numerous other accolades, becoming a staple on critics’ “Best of the Year” lists and looking more like an Academy Award hopeful every day – especially in light of its 10 nominations at the Golden Globes. Inevitably, that places its “transness” (both that of its story and of its leading lady) squarely into the public spotlight, since it will doubtless be a point of discussion come Oscar time.

As to that, it might be argued that Audiard’s film does not provide the most relatable trans representation by making its lead character a cartel boss, or that its story doesn’t really address issues of everyday trans experience – though we would counter that point by observing that one of the goals of queer inclusion in films is for queer characters to appear within stories that are not necessarily in themselves about being queer. In any case, there’s no denying that Gascón’s star turn is a breathtaking high point in trans visibility on the big screen, and mostly for its dedication to revealing Emilia’s layered humanity – something informed by her transness, to be sure, but not defined by it.

In any case, whether you come to “Emilia Pérez” for its transness or you don’t, it’s a refreshingly unorthodox piece of filmmaking that will leave you dazzled, and that matters more than all the awards in the world.

It’s time again for the Blade’s annual round-up of our favorite films of the year – and as always, we’re keeping our focus queer. We’ve loved movies like “Anora” and “The Brutalist,” and we appreciate the queer talent in inclusive titles like “Sing Sing,” “Emilia Perez,” and “Wicked,” but we’re limiting our choices to films that speak more directly to queer experience – which means most of the titles on our list are smaller movies that might have slipped under your radar.

Fortunately, we’re here to fill you in on the ones you missed.

#10 Cora Bora. Landing at No. 10on the list is a comedy-of-awkwardness, this time focused on a bisexual musician (Meg Stalter) whose faltering bid for success in Los Angeles prompts her to return to her native Portland and attempt to reconcile with the longtime girlfriend she left behind. Stalter infuses the clueless self-absorption of her character with a subtext that wins our hearts before we even know the backstory which illuminates it, and the overall tone of compassion that director Hannah Pearl Utt drives home a healing sense of “meeting people where they are” that makes us think twice about judging even the most insufferable among us.

#9 Big Boys. Equal parts bittersweet coming-of-age story and uncomfortable-yet-endearing comedy, this festival-circuit fave from filmmaker Corey Sherman strikes gold with an eminently relatable narrative about the awkwardness of burgeoning sexuality and a winning performance from young star Isaac Krasner, as a plus-size young teen who develops a crush on his female cousin’s hunky-and-bearish new boyfriend (David Johnson III) during a camping trip. Funny, poignant, and yes, heartwarming, it’s a much-needed look at the difficulties of navigating the transition to adulthood while also struggling with issues of body-positivity and sexual identity.

#8 National Anthem. Though it garnered little attention during its brief theatrical release, this indie debut feature from Luke Gilford deserves due attention for its remarkably jubilant story of a young day laborer (Charlie Plummer) who takes on a job at a ranch run by queer rodeo performers, including Sky (Eve Lindley), a captivating trans girl who stirs feelings he’s kept hidden at home. An open-hearted coming-of-age story, with an optimistic attitude toward acceptance, love, and finding one’s “people,” it’s a welcome must-see in a time marked by conflict and divisive thinking.

#7 Love Lies Bleeding. A throwback to ‘90s lesbian neo-noir, this stylized thriller from director Rose Glass stars Kristen Stewart as the estranged daughter of a small-town crime boss (Ed Harris) whose romance with an aspiring female bodybuilder puts them both in her ruthless daddy’s crosshairs. Pulpy, violent, and unapologetically amoral, it’s both an exercise in neon-tinged period style and a loopy-but-suspenseful thrill ride that keeps you on the edge of your seat even through its most absurd moments.

#6 The People’s Joker. Trans filmmaker Vera Drew wrote, directed, and stars in this off-the-beaten-path triumph that amusingly asserts itself as a parody in no way associated with any “official” comic book franchise – even though it takes place in an alternate, dystopian America where Batman is the president, comedy is regulated by the government, and a trans comedian named “Joker” is attempting to disrupt the system by organizing a band of outsider comics into an illegal comedy troupe. Ingeniously creative with its low-budget resources, it inverts all the revered comic book tropes and spoofs them through a radical trans/feminist lens — which may explain why it never played at your local multiplex — in a way that manages to be as hilarious as it is militant.

#5 Problemista. If there’s any queer creative talent that’s exerted a unique mark on the contemporary cultural landscape, it’s that of Julio Torres; this oddly conceived riff on the “buddy comedy” – his feature filmmaking debut – is a quintessential example of its fey magic. Centered on a young Salvadoran immigrant (Torres) with dreams of becoming a toy designer and his unlikely alliance with an art-world outcast trying to manage the estate of her cryogenically frozen husband (Tilda Swinton), it’s a “Devil Wears Prada” style coming-of-age tale about mentorship that simultaneously skewers the lunacies of modern American society and encourages us to look beyond each others’ surfaces to discover who we really are – a delicate balancing act which Torres pulls off perfectly, with invaluable help from a deliciously over-the-top performance by co-star Swinton.

#4 Femme. This sexy revenge fantasy from the UK, helmed by first-time feature directors Sam H. Freeman and Ng Choon Ping, centers on a London drag queen (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett) who undertakes a dangerous plot to “out” his attacker in a gay bashing incident (George MacKay) after encountering him in a gay sauna – only to find himself becoming entangled in a secretive relationship with him. With a title that hints at the pressures of “passing” in a homophobic world, and a convincing pair of performances to sell its premise, it’s an unexpectedly powerful (and transgressively romantic) thriller about the conflict between empathy and hate.

#3 Housekeeping for Beginners. Our third spot goes to this rich ensemble piece from the Republic of North Macedonia and rising filmmaker Goran Stolevski, which explores and celebrates the true meaning of “family” through the saga of a lesbian who agrees to adopt her terminally ill partner’s teen children, and then has to make good on the promise with the help of a household full of disparate outsiders she has collected around her. It transcends genre, blending social commentary with slice-of-life intimacy for a multi-faceted tale of queer resilience, and scores extra points for examining prejudicial attitudes around the “other-ized” Romani community in Central Europe.

#2 I Saw the TV Glow. Nonbinary writer/director Jane Schoenbrun takes an even more surrealistic approach with this unsettling horror tale in which a sensitive teen boy bonds with an older lesbian classmate over a bizarre late-night TV series – “The Pink Opaque,” about a pair of psychic twins who fight monsters together from opposite sides of the world, which goes on to have an unexpected impact on their lives. It’s difficult to explain the plot, really, but that scarcely matters; in the eerie, dream-like world it inhabits, memory, perception, and reality are interchangeable enough that it somehow all makes sense – and a metaphoric subtext emerges to build an obvious allegory about the mind-altering influence of pop media, the erasure of Queer history, and the crippling impact of cultural transphobia. The ending will haunt you forever.

#1 Queer. Topping our list is Luca Guadagnino’s lush big screen adaptation of William S. Burroughs’s semi-autobiographical novella, in which Daniel Craig is flawless as an American expatriate falling hard for a much younger man in the hedonistic haze of 1950s Mexico City. Raw and impressionistic, with frequent flourishes of surrealism and an overall tone of melancholy, it’s hardly a crowd-pleaser. But its fearless intensity and unwavering authenticity are palpable enough to burn – and we’re not just talking about the much-publicized sex scenes between Craig and co-star Drew Starkey, who also turns in an excellent performance. It’s a film of sheer cinematic beauty, a hallucinatory journey that touches human experience at its most intimate and essential level, with a career-defining star turn to anchor it.

As Tammy Wynette once sang, sometimes it’s hard to be a woman.

That iconic understatement might easily serve as the thesis statement for “Nightbitch,” the new horror-tinged offering from writer/director Marielle Heller. Yet while Wynette was lamenting the hardships of staying loyal to a partner, Heller is more interested in the hardships of staying loyal to one’s self – and takes on a rarely aired perspective on an even more quintessential feminine experience.

We’re speaking, naturally, of Motherhood, considered a definitive part of female identity ever since there have been women. Cloaked in sacrosanct reverence due to its association with the traditional imperative to “preserve the species,” it’s often seen as a rite of passage that illuminates and reinforces the traditional role of women as “givers of life,” and usually characterized as demanding deep personal sacrifice — the sublimation of oneself for the sake of another (who, in the words of Heller’s protagonist, would “pee in your face without blinking”) in obedient servitude to the greater good.

Before you start clutching your pearls (“How DARE you suggest that being a mother is anything less than a blessing?!”), we’re not knocking motherhood; nor are we suggesting that children are life-sucking demons who exist only to torment us and disrupt every facet of our lives until we feel enslaved by them. Neither, in fact, is Heller’s movie, despite the clucking of anti-“woke” commentators who have tried to dismiss it as feminist propaganda.

Indeed, “Nightbitch” is very much cognizant of “walking the line” when it comes to its inarguably challenging meditation on the demands of being a mother, though it dares to transgress societal dogma around the subject nonetheless. Based on the 2021 novel of the same name by Rachel Yoder, it’s the story of a woman (Amy Adams) who has “paused” her promising career as an artist to be a stay-at-home mom so that her husband (Scoot McNairy) can focus his energies on the job that keeps him away in the city for five days – and nights – out of every week. Rigidly defined by banal routine, her daily life is dominated by serving the needs of their child (Arleigh and Emmett Snowden, dual-cast twins in a single role), and weekend reunions with his dad seem only to reinforce the disconnectedness in their relationship, not to mention their parallel-but-discordant understanding of what it means to be a parent, a partner, and a person, all at the same time.

The situation is bad enough as it is when we meet her, an endless loop of sleepless nights, repetitive feeding rituals, and putting on her bravest face around the implausibly perfect other moms who congregate around her with their toddlers for storytime sing-alongs at the library. Things start to take an even more depressing turn for her, however, when she begins to notice strange physical anomalies – new and oddly located patches of hair, a heightened sense of smell, an increased appetite – taking place in her body. Though she at first shrugs them off, these changes soon escalate to include uncontrollable outbursts of aggression, resurfacing memories of her childhood and her own mother, and recurring dreams of nocturnal runs with the neighborhood dogs, who in waking life have become inexplicably drawn to her. Recognizing that these new developments might threaten the already delicate balance of her domestic status quo, she decides to seek answers – and discovers an arcane and disturbing secret history that stretches back across generations of mothers before her.

Hinged on a premise that naturally points in that direction, “Nightbitch” is handled by Heller as if it were a horror film – which, to a certain extent, it is – and unfolds through a carefully stacked progression of generic tropes as blatantly as any “Friday the 13th” sequel. Yet while certain moments do provide us with unexpected jolts and the gross-out “body horror” elements definitely strike notes of revulsion, it operates in a manner that more closely resembles a dark satirical comedy flavored with magical realism. Adams’s character (billed simply as “Mother”) accepts these alarming changes with as much detached resignation as she does the rigors of rearing her child, but her narrative moves definitively into action when she decides to embrace what is happening to her, drawing inspiration from the wilder self that is pressing from within to make bolder, more instinctual choices.

Ultimately, of course, the film’s lycanthrop-ish trappings serve as a metaphor for an inner beast kept caged inside that clamors to be unleashed. Its central character – who, as we see in flashback memories, was raised in what many would call an “extreme” conservative environment – has built an entire self-actualized life and abandoned it, over a traditionalist sense of duty, for something that feels like an existence of endless servitude. Why wouldn’t she feel the need to assert her natural autonomy?

And yes, there’s an obvious feminist message that emerges as “Nightbitch” lopes toward its denouement, yet while it mercilessly explores the grueling side of child-rearing and throws subtextual shade at the patriarchal attitudes that make the experience even harder, it works to reconcile all those seemingly dissonant viewpoints and reinforce the notion that being a mother is a path to self-actualization.

Heller keeps the root of the Mother’s strange transformation enigmatic, but her film could not be clearer about its purpose: spurring her protagonist to reclaim her autonomy, and to forge a balance between her roles as an empowered woman, a selfless mother, and an artist with the potential to reconcile them all into one. If, that is, she can keep herself from going feral.

Adams, whose talent as an actress has often been underappreciated despite critical acclaim and multiple industry accolades, shines here in a way she’s previously never been allowed, taking on a glamourless yet compelling role and embodying it without reservation or ego. Her character walks a razor’s edge of likability, but she brings the kind of truth to her performance that keeps us on her side. In a similar fashion, Scoot McNairy (billed as “Husband”) manages to represent “The Patriarchy” yet also surprise us with his adaptability and empathy; together, they embody a couple we are somehow happy to root for, whose relationship – like all relationships – is a work-in-progress. The ‘70s cult cinema icon Jessica Harper also makes a significant impression as a vaguely “witchy” librarian who facilitates Adams’s quest for knowledge.

The quality of these performances – and Heller’s meticulous crafting of the film, which mostly keeps its supernatural elements in the nebulous realm between real life and imagination, though there are some legitimately disturbing moments – help to push “Nightbitch” beyond its genre pretensions and use it to express feelings that will doubtless be familiar to millions of woman, yet rarely explored onscreen. Viewers looking for horror might see this as a “bait-and-switch,” but it’s this frankness that distinguishes it, especially in a time when women might well be facing the real horror of a future without bodily autonomy.

If that’s not enough to make it one of the season’s essential films to see, then it should be.

-

Arts & Entertainment3 days ago

Arts & Entertainment3 days ago2025 Best of LGBTQ LA Readers’ Choice Award Nominations

-

Local3 days ago

Local3 days ago‘Think of those who have not been seen,’ Cynthia Erivo’s powerful message at GLAAD Awards

-

Opinions3 days ago

Opinions3 days agoGay bar in California bans MAGA gear — but no other political expression — from its premises

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoTristan Schukraft speaks on keeping queer spaces thriving

-

California2 days ago

California2 days agoGLAAD’s Latine Honors celebrates culture and identity with packed house

-

California1 day ago

California1 day agoTwo anti-trans bills fail to advance in California

-

Arts & Entertainment3 days ago

Arts & Entertainment3 days agoTrans Day of Visibility: Let us put you on 5 Latinx musicians you should be listening to right now

-

opinions9 hours ago

opinions9 hours agoCory Booker’s missed moral moment

-

Movies1 day ago

Movies1 day agoSexy small town secrets surface in twisty French ‘Misericordia’

-

a&e features9 hours ago

a&e features9 hours agoCreator Max Mutchnick on inspirations for ‘Mid-Century Modern’